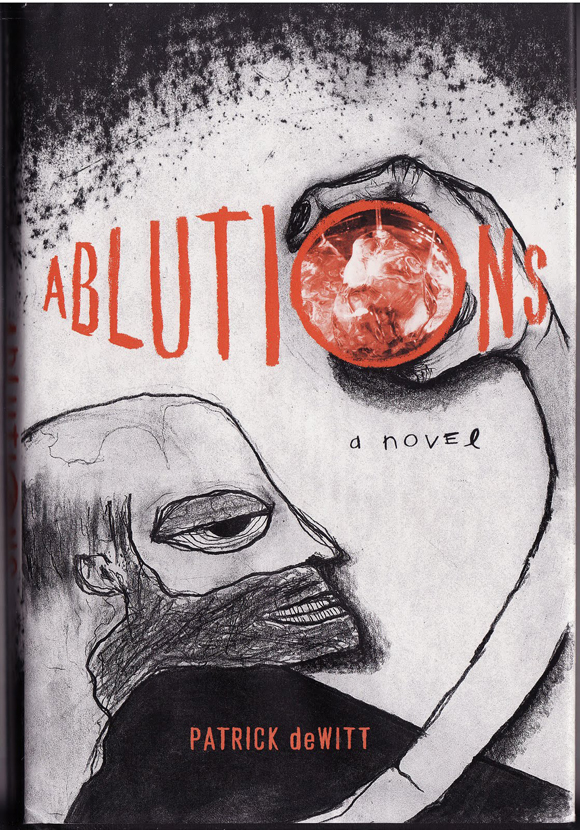

Told in second person, Ablutions begins with the narrator “discussing” the regulars. A wannabe cop with Vitiligo, a dubious medium with a long grey beard, a South African ex-pat ex-male model, a former child actor bloated, bleach blonde and hopelessly warped by his childhood in the spotlight, a parasitic-yet-lovable crack addicted giant, characters that have nothing and no one in their lives more important than themselves and the seedy LA bar in which they spend most of their time. Through the lens of an alcoholic bar back, the narrator has brings the audience into the world of the bar just before his life and the lives of the regulars begin to spiral out of control. Jobs are lost, lives are threatened, prostitutes are hired, marriages are dissolved and horses are, without warrant, beaten and shouted at.

On paper, the premise of Ablutions looks like it was dreamt up by a young man aspiring to the romanticized archetype of the drunk writer: notes for a novel regarding alcoholism, spending one’s life in bars and drinking dangerous amounts of whiskey and consuming a brain-baking amount of drugs. At best, the premise feels like well-worn territory and, at worst, tedious and uninteresting to anyone over 21. However, DeWitt possesses the skills to transcend the stereotype: an annunciated wit that seems inherent to people from the northwest, an insight into the actions of addicts and the ability mold them into crystalline aphorisms that demand underlining.

Regarding the narcotics-addicted pharmacist woman who the narrator believes is actually a pre-op transsexual male, “She has asked you many times to walk her to her car or to the ladies room, and has asked to accompany you to the storage room, but you always say no because there are certain mysteries in the human world that you have never been curious about and here is one of them.”

The wisdom of an institutionalized drifter, “There are two types of people: Those who want to cry, and those who are crying already and want to stop.”

Regarding the narrator wishing a regular’s death, “Simon is staring at you, and now he knows for a fact something he has suspected for years which is that you have a streak of hate in your heart and that it is deep and wide and though you have hidden it, it is unmistakably uncovered now, and he will never feel that previously mentioned fondness for you again and you can see the words in his eyes as plain as day: I’m going to get you fired from here, mate.”

Most impressive about deWitt’s style is how he recognizes the importance of showing images rather than expositing. Describing a tall man the narrator becomes briefly obsessed with, “He is leaning against the wall of a convenience store and you see his wide hat and dark clothing and know he could cross the street to you car in two long strides and you think of him following you home and crawling through your front door on his hands and knees.”

The idea of notes for a novel may come off as lazy, as if the writer didn’t feel the need to flesh out the story or characters all the way, but instead decided to hand the audience a bunch of ideas and leave it up to them to piece it together. This isn’t the case with Ablutions. The notes aspect offer the audience the immediate intimacy of reading someone’s journal, as if the narrator immediately trusts us, and in turn, we must trust him to take us somewhere interesting.

When you spend lots of time in bars, drinking and operating under the delusion that you’re going to one day be the next Fante or Faulkner (a romanticized lush in your own right) you collect all these strange things that happen in bar culture as if they mean something, as if they can be used for your writing at some point. The drawback is that the things that happen in bars often only add up to a few anecdotes, some jokes, and maybe a good story to tell a stranger who drags a seat up next to you. However deWitt pulled something interesting off in Ablutions with these collections of abuse, of violence and self destruction: he painted a larger picture of pain and suffering and the depths of denial that human beings are capable of when they stop taking responsibility for their lives. DeWitt highlights the point that those are the moments that can come to define us as humans and he asks the audience this question: What kind of human are you? The kind that succumbs to the horror of your pain or the kind that propels yourself out of it?