Author, editor and activist Anne Elizabeth Moore dropped me an email a few months back and told me about the LADYDRAWERS project, an exhaustively researched graphic essay series focused on gender inequalities in the comic book publishing world, working with (and from) interviews with Alison Bechdel, Ariel Bordeaux, Lynda Barry, Julie Doucet, and other comics artists you have and haven’t heard of before. The series had already run in Bitch, Tin House, Women Comics Anthology and was soon to be a monthly column at Truthout.org. She asked if I wanted to run an installment in the new issue of Annalemma. I said hell yes.

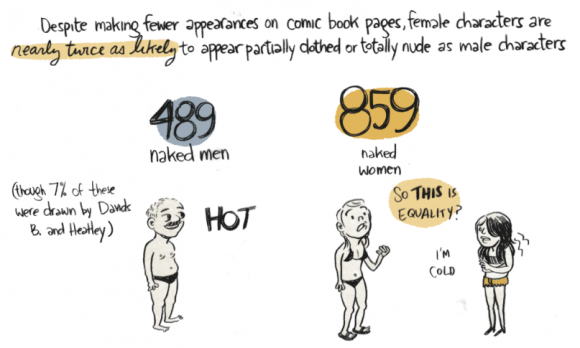

A few weeks later, Anne delivered the the latest installment illustrated by Susie Cagle and I was shocked at the stats brought forth in the essay. Let’s just say it’s a lot worse than you think.

Anne is the author of Unmarketable (The New Press) and was the founding series editor of the Best American Comics (Houghton Mifflin). She received a Fulbright this year for her work on global media and youth culture in Cambodia. Her book Cambodian Grrrl is forthcoming in September from Cantankerous Titles.

We had a chance to speak over email last week. If you’d like to check out, Where the Girls Aren’t, latest installment of the LADYDRAWERS project click here to pre-order Annalemma Issue Eight: Creation.

ANNALEMMA: I was listening to the Matthew Filipowicz show and you said the idea for the LADYDRAWERS project started while you were on tour with Harvey Pekar promoting the Best American Comics series when a group of male fans crowed the stage to get Pekar’s autograph, subsequently shoving artist, Esther Pearl Watson, off the stage. Was this the breaking point for you? What other events leading up to the project inspired it?

ANNE ELIZABETH MOORE: No—they were male cartoonists. Really smart, strong, talented, kind people who would also consider themselves feminists. That’s the thing, and it happens everywhere, not just in comics: dudes shutting women out completely by accident, even when they would claim, otherwise, to be supportive of diversifying their own areas of interest. I had experienced that personally a zillion times, but this was different because I could see, objectively, how completely accidental it all was. So I guess this incident wasn’t so much the breaking point as the first time I had someone else to talk to about how deeply embedded regressive gender norms are in this field that’s supposedly about opening up the potential for communication.

Up to that point, I was only experiencing this stuff from the receiving end—getting silenced, many times quite deliberately, by male creators who dominate the field. But here it was like, I was in a position of authority, and I respected everyone there. This was my book, and I’d established a structure for these events that was deliberately inclusive of women artists, and had made a point of openly addressing this: I saw the Best American series not just as a way of celebrating amazing work but reestablishing a center for comics, like, reevaluating the different directions the field could move in. I think that’s why people are still buying that first book, it was a really exciting idea both Harvey and I embraced. And there it was, a talented female creator getting silenced in my presence at my event by other people who totally respected her. That’s when you know there’s a problem significantly larger than one person can change.

A: The scope of the project is pretty impressive, seeing that you’ve published installments in a range of different magazines and now lead a class on the issue. How does the university class fit into the project?

AEM: Well, I have these vague research ideas and then I work them in a milion different directions at the same time, that’s just sorta how I do things. As I say I’ve been collecting anecdotes related to gender and comics over my twelve-or-so years in the field, but having this shared crazy experience with Esther meant we could chat over ideas and ways of representing and addressing them. After that, I started doing some polling and collecting data from women and trans people in the field, and then pitched this class in the Visual Critical Studies and Art History departments at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and that’s been running for two years. The students sort of help me sort out different ways of gathering information around hidden bases of knowledge, and then we research, collaboratively.

Last semester we had a really incredible class that ended with us wanting to share our research with the publishers directly, and the postcard project came out of that. This summer was the first time we got to work together and look at that data in a studio course—make art out of it. Of course Esther came with me and we spent a couple weeks at art camp, basically out in the woods, making super crazy gender and media theory comics. It was the funnest thing ever. We put together a handbound anthology, Unladylike, that is smart and fun and gorgeous. Working with students on these issues has been the funnest part of this project. Everyone goes into those classes super bummed about institutionalized sexism, really feeling at the mercy of it, YES even the dudes, and then they leave the class with facts, strategies, experience, and a sense of humor that they can apply not just to comics but to the other fields they work in—video games, journalism, art, theory, etc.

I’ve also been pulling in these other artists and asking them to work with me on parts of the big picture that maybe they relate to more closely. That’s sort of the above-board aspect of this work, and the Annalemma piece was a part of that, and also a bimonthly column for Truthout that just launched. Work like this—media-based, anti-oppression work—it just takes a lot of different approaches, each of which serve a consistent reminder that stuff needs to change, not once, but every damn day. Plus that these regular outlets serve to establish a forum for young creators that will be there when students enter the field—my own students, and the students I speak to when I lecture elsewhere—that’s really important. That means, you know, we’re not complaining about a problem, we’re developing shared vocabulary about one that we are also changing at the same time.

Panel from “Gender and Comics Potluck,” Esther Pearl Watson and Anne Elizabeth Moore, Bitch Winter 2011

A: Installments of this project frequently reference the now-famous VIDA numbers where it was pointed out the literary publishing community operates with a strong bias towards publishing and promoting the writing of men. What the VIDA numbers didn’t address was how women are portrayed in writing. The LADYDRAWERS project attempts to tackle the issue of how women are portrayed in comics, as well as the issue of how many women are employed/published by the industry. Which is more important to you?

AEM: Yeah—I think that’s a more relevant issue in comics than elsewhere, basically because the ways that women are portrayed do, we know from studies and from anecdotes, turn off both readers and creators, and both women and trans people, but also other people who are just gender aware. So content matters in some fundamental way right now across comics more so than literature in general. But the important things for me are establishing these issues as labor issues, because that’s where most of the laws that govern these fundamental concerns are made tangible. It’s one thing, in other words, when a comic shows a lot of gratuitous naked boobies, but it’s another thing when a comic-book publisher is committing gender-based discrimination or sexual harassment to do so. One’s annoying, the other is legally actionable.

A: The interesting/confusing thing about the bias towards men in the lit publishing world is that influential positions within the industry (editors, publicists, PR people, etc.) are dominated by women. The opposite is true for comic book publishing. One of the more interesting stats you provided in the Where the Girls Aren’t was that of the 1,112 jobs in comic book publishing, 85.43% of those jobs went to men. Why do you think all these jobs are going to men?

AEM: Women totally “dominate” literary publishing, it’s true, and that’s really important to point out. These problems, of inequity and gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, exist everywhere, but really flourish in comics, which are traditionally seen as underground and alternative, but also informal and unregulated and slightly outside the law. So that situation in literary publishing that still allows men to receive most of the slots available for creative work, and therefore most of the income that supports that as a career, that’s just more tangible in comics. Comics are a form of media, which should be beholden to the same principles other media in the US should be held to, that it represent readers, that it remain open to new participants, that it engage in an active relationship with the world. Why it doesn’t happen in the literary world is how institutional sexism plays out: small decisions, made every day, supposedly automated by policy and technology and language and standard modes of operation that very, very slightly are also discriminatory. It’s much more obvious why this doesn’t happen in comics because we can trace all the players. Why do they hang out with? Who do they model business practices on? Who do they drink with? Who do they work with? Who do their creators recommend? What does the content of their work show that their website’s “About Me” page doesn’t? That’s what institutionalized oppression is: the thousands of tiny decisions that collectively favor one group of speakers/decision-makers at the expense of others.

A: What do you say to the argument that gender inequality in the comic book world is symptomatic of a larger patriarchal system that favors men over women? Why go after the comic book industry for catering to men? Does it ever feel like there’s bigger fish to fry?

AEM: Well, sure, it’s symptomatic of a larger problem, and the next level up of it is referred to as “a patriarchal system,” but the big picture here is pure capitalism. This work closely examines one of the very jarring but popular ways that capitalism operates, every day, that we don’t notice. It points to some negative effects for creators, for readers, and for democracy in general. It presents a few obvious solutions, and opens up more questions within those, all backed up with a real and newly collected data pool to which hundreds of people (or more) are contributing to around the country in the direct hope to change something that they aren’t wholly comfortable with. If there’s a bigger fish to fry than the daily, grinding, unseen, negative effects of capitalism, I don’t know what it is.

A: Can you give us a reading list of titles that are doing things right? What are some good reads written by women and/or feature strong female leads?

AEM: I can’t. This is a deeply embedded issue, and it’s been going on for a long time. We simply haven’t seen very many women, trans, and queer creators besides those that everyone already knows about (who ARE great) flourish, and until there are a plethora of non- straightwhitemale types reinventing what language could be in comics I refuse to forward single names or publishers. I should also say, though, that I’m pretty selective about who I collaborate with on the literary and journalistic strips, so everyone I’ve worked with on the BITCH, TIN HOUSE, ANNALEMMA and TRUTHOUT pieces make great fucking work, and I literally have hundreds more underrepresented women, trans and queer creators lined up to work with in the coming months. There’s still room for more though so if you make comics, and you are awesome, and we are not already working together, send me your stuff at artshowheckyeah@gmail.com.