The new Hobart provides stark insight into the difference between publishing fiction in print and publishing it online. A hallmark of online fiction is that it’s short. It’s written and published with the mind that you’ve 50, maybe 100 words to hook a reader, after that you’d better keep a tight grip on their lapels for the other 900 words if you’re going to keep them reading to the end. There’s plenty of juicy celebrity gossip and cat videos out there to compete with, so you’d better not waste anyone’s time. This constraint can be motivating for a writer, but a lot of tasty storytelling elements can get thrown out the window when trying to whittle everything down to a palatable 1000 words. Things like slow pacing and deep characterization.

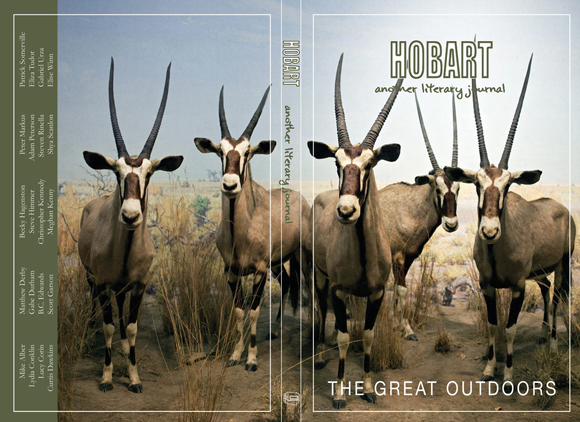

The stories in The Great Outdoors issue of Hobart remind you why it’s rewarding to read a story in print. These stories turn down the volume to the outside world and take their time letting their horror and beauty unfold. They remind you that stories can be more enjoyable as a slow burning wick, instead of a buckshot blast.

Highlights:

4 Outdoor Apocalypses by Lucy Corin

Corin’s work in this issue kind of negates everything I just said as none of them are above 1000 words, but these four short pieces show a larger picture of a destroyed world. My favorite, Glass, moves fast: a new plant species that’s sharp like glass is taking over the world, infecting the world in its shards. Corin keeps her scope wide with this one, dropping in detail when she needs to and quickly moving on. It’s not so much cursory glance as it is showing the audience what’s important and nothing much else. I’ve lost my taste for apocalypse fiction, but Corin pulls out a beauty in the end of the world while many writers are content to wallow in despair.

The Fish by Patrick Sommerville

This one’s the prime example of how fulfilling a story can be when a writer takes their time. Ben returns to his hometown to visit his estranged mother who’s on the brink of death. He runs into Carl, a friend of his mothers who ran a successful fishing business until a Japanese executive suffered a horrible accident on one of his trips. Years later the two men are in different stages of disrepair: Ben is worried about being stuck in this town forever, and Carl is simply stuck, unable to recover and rebuild from the accident. The thing I love about this story is Sommerville never uses exposition. If there’s something profound that happened to a character, he’s going to take you back and show it to you in a scene, because it’s important and deserves more than a cursory glance or an offhanded mention.

The Lake by Becky Hagenstan

David, another broken young man, makes a trip out to visit his father, another shattered old man, who’s taken to living out in a cabin in the woods by himself after a series of defeats has caused him to withdraw from life. David goes out there on the pretenses of delivering a gun the old man kept in David’s basement. The old man claims it’s for shoo-ing away bears, but when David gets out to the cabin he soon learns it’s for a far more bizarre reason. In The Lake, Hagenstan shows how a father can disappoint a son and vice versa and that the only answer is to forgive and move on, otherwise the bitterness with consume you like a prehistoric beast creeping above the surface of the water.

Congrats to editor Aaron Burch. He’s compiled a damn fine stable of writers this time around, not surprising considering Hobart is one of the most reliable journals out there for quality stories.

speaking of the great outdoors, I just wanted to wish all the Annalemma readers in NYC a Happy Manhattanhenge Day 🙂