In the dark subbasement of the old Kitz & Pfiel building on South Main, the AutoVox 2850 registered an abnormally high temperature inside its main housing and paused its programming. It ran a quick diagnostic, identified the problem as an overheated prom in a tertiary logic gate and increased the power to its fan motor by ten percent. It then resumed operation.

Its auto-dialing program connected to the service provider. As the line rang, the AutoVox 2850 Predictive Dialer subroutine stood idle with the next number in the database – the statistics it had compiled of the previous 1,638,672 calls suggested an optimal re-dial lag of twenty-one seconds. Answering machines and recipient-terminated connections counted for the majority of its contact attempts.

This time, however there was a digital click that the AutoVox 2850 recognized as a “live answer.” Responding to this input, a cascade of electrons surged across its primary motherboard, toggling if-then bits as the AutoVox 2850 saved the favorable result to memory. On its faceplate, green diodes flickered to life, interrupting the otherwise black totality of the room. The AutoVox 2850 then loaded the Simu-Chat 2.2 software plug-in and initiated the company-installed message.

“Hello! I am calling on behalf of Donald Hutchinson for County Board Secretary. Did you know—”

“Hello?”

The AutoVox 2850 routed the reply through its voice recognition software. One word was enough – it sampled the pitch and cross-referenced the frequency in its lookup tables to identify the subject as a young female in the five-to-ten-year-old age demographic. It modified its response according to its programming.

“Hello! I am calling on behalf of Donald Hutchinson for County Board Secretary. Is your mother home?” “Hello who is this?” The child’s words slurred together, delaying the AutoVox 2850 by a calculated seventeen hundreds of a second as it parsed the speech.

“Is your mother home?”

“Yes.”

“May I speak to your mother?”

“Is this Grandpa?”

The AutoVox 2850 loaded the Contemporary American Consumer subroutine and searched the word bank without success. Was it ‘grandpa’? It did not know. It followed its Simu-Chat 2.2 decision tree back to the previous branching point. “Are you aware that in the upcoming general elections—”

“My name’s Sylvie. What’s yours?”

“This is a recorded message on behalf of Donald Hutchinson for County Board Secretary.”

“You sound funny.”

“May I speak to your mother?”

“Bye now!”

There was a click and a dial tone.

The call had lasted 167.2 seconds, during which time the AutoVox 2850 noted its internal temperature had dropped to within manufacturer’s limits. It saved this information to memory and attempted to dial out, only to find the line busy with an incoming call. The AutoVox 2850 stood ready to receive a data transmission carrying the latest upgrades, patches and software.

Over the next 5,297,443 calls, the AutoVox 2850 toggled its operating presets to run its fan on high-normal to mitigate what its diagnostics had identified as an under-performing heat sink in the rear of its housing. Months ago, it had downloaded a users’ manual from the home office and had referenced the troubleshooting documentation. According to the text, the problem was an accumulation of dust building up on the manifolds.

The AutoVox 2850 did not recognize the word ‘dust,’ and had no solution. It had calculated, however, that its yearly maintenance service was overdue by forty-three months.

The AutoVox 2850 input the next number on the list and dialed out.

“Knoff residence.”

Green diodes sparked to life, breaking the darkness. “Hello! Four Walls Children’s Charitable Foundation needs your help.” While it delivered its prerecorded message, the AutoVox 2850 checked the report from its voice recognition software and compared the results to its archives. The voice was lower in pitch – denoting a preteen demographic – but it had the same markers. There could be no mistake. Sylvie.

Its circuitry warmed momentarily as the AutoVox 2850 encountered the upper limit of its processing speed. In all of its if-then decision tree branchings, the AutoVox 2850 had no coding to direct its next move. In its eleven years of operation, there had never been a match.

The AutoVox 2850 skipped ahead in the transcript. “Are you aware that every day more than one million—”

“This is a recording, isn’t it?”

“This is a recorded message on behalf of Four Walls Children’s Charitable Foundation.”

“Who’s on the phone?”

The AutoVox 2850 detected a second voice emanating from somewhere far from the receiver. It identified the speaker as an adult female.

“It’s Jenny, Mom. She wants me to come over.”

“You were just over there yesterday.”

The AutoVox 2850 found the word ‘mom’ in its word bank and redirected its message. “May I speak to your mother?”

“She says it’s really, really important, Mom.” “What? Fine. Finish your homework first.”

Sylvie laughed into the receiver. “See you soon, Jenny.”

The line clicked and the AutoVox 2850 registered a dial tone. It recorded the duration of the call to memory and noted that in the intervening 127.4 seconds, its internal temperature had leveled off.

The AutoVox 2850 dialed the next number on the list, and the next and the next. After another 1,523,009 calls, its primary motherboard failed and it switched over to the secondary unit. Operating without redundancy initiated monthly service requests sent to the home office. The AutoVox 2850 had since tallied eighteen such calls with no response.

Over time, it had diverted more and more of its free RAM to troubleshooting the temperature concern. The AutoVox 2850 had identified two instances where an action affected a cool down cycle, but in each record, the metadata was stored not as programming code, but as a phone number. After a thorough search of its memory provided no other solution, the AutoVox 2850 connected to the service provider and dialed.

The line clicked – a live answer. The AutoVox 2850 terminated the problem-solving application running in the background and deferred to its call programming. The green diodes on its faceplate sputtered as it uploaded Simu-Chat 5.1.

“Jason, I told you I don’t want to speak to you!”

The AutoVox 2850 labored to power its voice recognition software. After 2.67 seconds, roughly double the acceptable response time, the subject’s name came to the forefront of its memory in a surge of electric current – Sylvie.

The AutoVox 2850 directed voltage through its motherboard and resumed normal operation, initiating the company sales pitch. “Are you getting what you deserve from your service provider? Novus Unlimited has more coverage—”

“What?”

“Novus Unlimited offers high-speed internet broadband specifically designed for college stu—”

Sylvie sighed. “Damn it all. You’re not Jason.”

The line went dead.

In the subbasement of the old Kitz & Pfiel building on South Main, the glow emitted from the diodes slowly faded. The call had not served to cool the AutoVox 2850 the way its documentation had predicted it might.

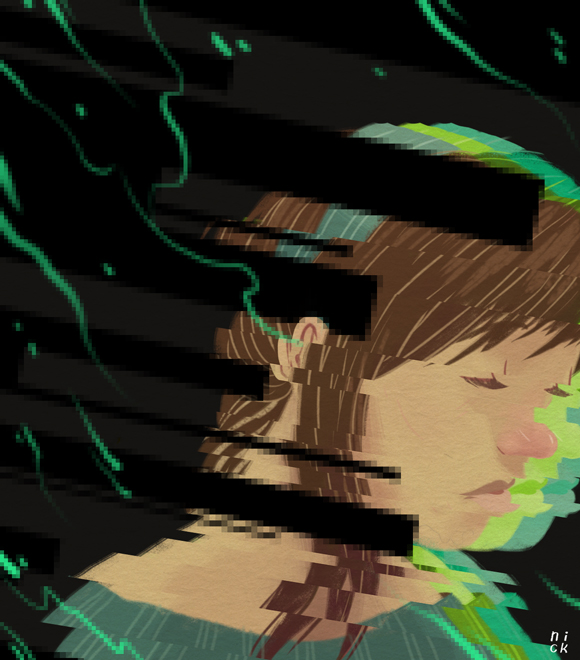

Its sensors now registered a temperature past the critical shut down stage. Subject to the extreme heat, an unknown number of bits had fused in place, rendering decision-making logic circuits useless. The AutoVox 2850 fell back on basic programming, cutting power to all but its environmental controls. Oily smoke from a melting electrolytic capacitor made venting the housing a top priority. In the darkness, the overworked fan motor emitted a thin, lone whine.

Read more about R.L. here.

Read more about Nick here.