Moments after the plane passed, Dad called. “Did you see that big bomber?” he said. I told him that I had, that I’d even hung my head out my car window to get a better look. “An old B-29,” he said. “Granddad used to test machine guns in them during World War II.” B-29s were manufactured at numerous U.S. factories; at one point, factories produced as many as one hundred bombers per day. My grandfather worked for Douglas Aircraft in Tulsa, Oklahoma at the time, so when the bombers arrived from the factories, Granddad got to fly in them when they were brand new. That was before the family did what so many Okies did after WWII and moved to Arizona in search of work. “There aren’t many of them still around,” Dad said. I thought, There aren’t many men like you around either, men who had lived through the War and could recount, from experience, the tribulations of the era: the rations, the gas shortages, the practice air raids during school. Men my father’s age – now seventy-one, officially an “old-timer” – like B-29s and propeller engines, are all suffering diminishing numbers.

I pulled into a drugstore parking lot to talk. Dad said, “It gave me chills seeing that.”

He recounted how, right in the heart of the war, everything was rationed. “Things weren’t looking good for us,” he said, “for the country. Everyone had their Victory Gardens to raise what they needed, so people planted fruit and vegetables on every inch of ground they had, that included the front yard. So in Tulsa we had this dog – I can’t remember his name – and every now and then he would come home with a live chicken in his mouth. Mind you, you couldn’t get chicken in Tulsa during the war. White rabbit was all you ate; it’s all they’d sell. Everything was rationed cheese, rationed butter, rationed meat, flour, lard. Everyone had a little ration book that you brought and checked off, every month. So one night I go out in front of our house, and there’s Dad kneeling down next to this dog, trying to pry his mouth open to get this live chicken out of his mouth. He’s kneeling down and he looks up at me – his eyes really wide, smiling – and says, ‘You know Joe, as soon as this war is over, I’m going to break this dog of this habit.” Dad and I laughed in unison at that. Granddad would have laughed too. He was the family’s biggest joker. “If he knew where this dog was getting these chickens,” Dad said, “he never said where.”

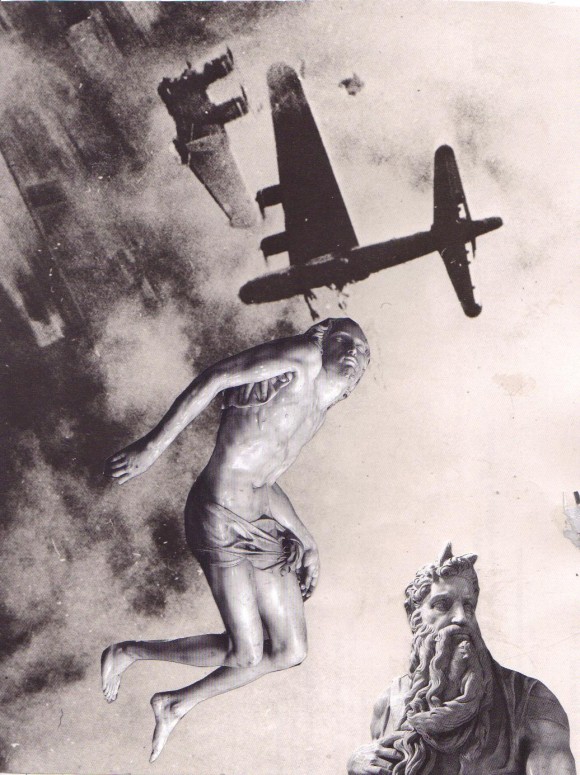

The bomber glided north, just a shining silver dash blending into blue sky. Sometimes you have to see history to comprehend it.

Dad said there used to be a Naval Air Facility in the town of Goodyear, Arizona, outside Phoenix. Constructed during WWII, the vast property stored excess and obsolete U.S. Navy, Coast Guard and Marine Corps aircraft whose usefulness had passed with the rise of the jet engine. The 800-acre facility was filled with grounded planes, at one point over 5,000 of them. B-29s, B-52s, B-17s, B-19s, any you could imagine, all lined up side-by-side in the dry desert air. An airplane boneyard, people call it. “I wish I had taken a picture of it,” Dad said. “It was really a sight.”

Some of the planes were reused during the Korean Conflict, but after that war ended they were grounded again and the facility decommissioned. The planes sat in the boneyard for years, still as shed snake skins, rusting and aging in the relentless sunlight, until they were either shipped to another storage facility, sold or smelted, or meticulously stripped of their valuables. Stripped, the same way all of our bodies will one day be stripped by worms, beetles and probing roots. Maybe I’m being morbid, but lately it seems that we’re all destined for the boneyard, fated to lay still and obsolete.

Dad’s retired. Thanks to a lifetime spent eating starchy, salty, country cooking, he’s had three stents planted in his arteries, takes nitroglycerin spray for angina, and seven separate medications for high blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes, and related cardiovascular problems. He takes insulin shots now too.

I just turned thirty-five and can’t stop thinking how Dad’s time, like that bomber’s, has nearly passed. He built his career by building houses for Del Webb throughout the Sunbelt. He made a good living, raised five sons and bought a home, and now he stays in it all day and reads about Arizona history. He’s grounded but not out of commission.

At thirty-five, I sometimes think that I’m still young, then I remember that there is always someone younger and hungrier waiting in the wings. Like prop planes in the Jet Age, my youthful days are numbered. Our replacements shake our hands when they arrive for their first day of work, vigorous, eager men and women, just out of college, with visions of careers and retirement packages and lives ahead of them.

I stepped from my car and peered over the roofs of nearby houses, but the plane had passed from view. “You got a rare sight,” Dad said over the phone, “not only of that aircraft, but with it flying so low.” He paused, breathed into the phone. “Alright. Just wanted to say hi and see if you saw it.” I told him I was glad we’d both seen it, and I told him that I loved him, because in that bomber we both saw the same thing: time, quickly passing, stealing the things we love and the very people we want to remain forever.

Like the essay? Check out our print issue.

Read more about Aaron here.

Read more about Andrew here.

Gorgeous. Just fantastic.

Thank you.