The long line of cars waiting to enter the fairgrounds begins to move and Garrison edges forward in his seat, his forehead practically pressed against the hot windshield. I cannot believe how many people are here—I whisper the prison pressed license plate numbers from all over the country. I am wracked with a fresh wave of guilt. The world is overpopulated. The world is suffering. Here we are, with scores of other people who have also chosen to ignore these facts. We are all arrogant assholes.

“Maybe we don’t deserve to have kids,” I say.

Garrison turns to me. “What makes you say that?”

I can’t help but notice that he doesn’t disagree. I recite the litany of excuses people like us trot out to condemn our desires. “There are so many children out there who need good homes. Blah blah blah.”

He brushes his fingers along my chin but his touch is not gentle. “We’ve been over this.”

After we called the toll-free number, requested the informational DVD and brochure. After we requested the time off from our respective jobs and told our families we were going on a short vacation. After the second-guessing and hand wringing. Here we are. In our foul, humid Civic with the empty back seat, still infertile. I pictured a neatly paved road leading directly to the hallowed tent of Brother Marcus. He would be waiting for us, just inside the entrance. As we entered, his arms would open wide. He would pull us into an embrace. He would lay a hand on the flat of my stomach, whisper words I couldn’t understand. He would grip Garrison’s shoulder and counsel my husband on a man’s responsibilities. He would hold my hand and counsel me on embracing the joys of motherhood. There would be air-conditioning.

When we finally enter the fairgrounds and park the car, all we see are dusty, foot worn paths leading to a bright purple tent. I watch the throngs of barren couples around us, all seething with the same desperate urgency to procreate. Garrison and I look at each other. “We should just go home,” I say. Garrison gets out of the car, and slaps the roof of the car. “Like hell,” he says. “Brother Marcus is gonna make us a baby.” As I get out of the car, take Garrison’s hand, and head into the tent, I think back to my sixth grade biology class—the lesson on biomes. My womb is a tundra, unable to provide sustenance.

A wide, circular stage, three feet from the ground, sits in the center of the tent. It is brightly lit, yet sparse. In the center of the stage there is a large tub made of stainless steel, filled with rainwater, large enough for two adults. Brother Marcus believes in a wide variety of religious traditions, the brochure told us, and in that vein, he borrowed from the Jewish concept of mikvah, allowing his audience to cleanse themselves, purify the lives that had brought them to this point so they might conceive anew. A few feet to the right of the tub stands a mahogany pulpit with ornate carvings around the edges and above it is a large, flat screen monitor, suspended from the aluminum tent rafters.

Towards the back of the stage are bleachers, filled with women in varying stages of pregnancy, the mounds of their bellies taunting, teasing, gloating. Their joy is palpable. Behind them, their husbands stand tall, proud, smug. The evidence of their virility is incontrovertible. Surrounding the stage are hundreds of metal folding chairs, arranged in pairs for those of us who have flocked here, two by two. Already, the first few rows are occupied. Garrison and I make our way down a clear aisle and sit near the back where we can feel a slight breeze from an open flap in the tent. The air is tense and thick and filled with the stench of perfumes and deodorants, bodies and, oddly enough, onions. Around us, couples chat nervously but Garrison and I are silent. I hold his hand so tightly my knuckles turn white and he says, “You’re going to break my hand, babe.”

My husband and I often ask unanswerable questions of each other. Should we give up? Should we find other partners? Why are we putting ourselves through this? But now, we sit here, knowing we’re wasting our time, moving forward nonetheless. We hold on to the brittle hope that it will soon be me sitting in those bleachers, caressing my swollen belly, the glow around me incandescent. We hold this bitter hope but ask nothing more of each other. Somewhere along the blanched highways, between rest areas and mile markers, we found the answers to all the questions we are always afraid to ask.

The argument started miles south of Paris, Texas, when the heat finally pushed us to a new breaking point. The air in the car was so thick it hurt to breathe. I said that we needed a new car. He snapped, and pulled onto the shoulder, slammed his hand against the dashboard. He said, “Maybe we could afford a new car if we didn’t spend all our money chasing down new ways for you to get pregnant.” I said something about his job and future employment prospects. He said fuck you. I got out of the car and even though the sun was high and scorching everything around and between us, I started walking, ignoring Garrison as he followed. “Get in the damn car,” he said through the passenger window. I gave him the finger. I kept walking. He sped off, leaving an angry trail of rubber. I waited, hands on my waist, ready to resume our argument. He didn’t come back.

I walked all the way to Bogata, population 1,401. I found a bench, and fell into it. My mouth was so dry I couldn’t swallow. When I felt I could engage Garrison in a conversation without crying, I called him. He sounded panicked, demanded to know where I was, said he had been driving up and down the same stretch of highway for hours. After he picked me up, he apologized through clenched teeth, a lie. We stopped talking after that.

After an hour of waiting and sweating and listening to the couples around us reciting stories we already know, music starts playing. It is not the gospel we expect, but rather, rock and roll, dirty South, stripper pole rock and roll. I stifle a laugh, and the chatter hushes as a robed figure makes his way through the audience and walks onto the stage, standing before the steel tub. The figure raises his arms, and the hood of the robe falls to his shoulders. The audience instantly breaks into applause. It is Brother Marcus, his face shiny with sweat. His hair is as perfect as it was on the infomercial. He is the Pat Sajak of fertility. Wheel of Fortune, indeed. As he shrugs out of his robe, an assistant scurries to his side and disappears just as quickly. Brother Marcus rubs his hands together, and with a wide sweep of his arm, turns towards his success stories, sitting on the edges of their seats in the bleachers. “My work,” Brother Marcus says. “Speaks for itself.”

When Garrison chases after his nieces and nephews on Sunday afternoons, he smiles so widely that his features rearrange themselves to accommodate the stretch of his lips. He laughs from somewhere deep and when he finally catches one of them, he throws them over his head, their legs tangling with his arms. When we catch each other’s eyes in these moments, there is something bittersweet between us.

For the next few hours, Brother Marcus rambles on about God, fertility, sin and redemption, at a dizzying pace. There seems to be no logical connection between any two words, and yet, the audience is captivated, hanging on to his every word as if there is a mystical meaning to be divined from the incomprehensible babbling. I have grown weary beneath the weight of his words. I press my hands to my womb, imagining a fluttering that is not there. Garrison occasionally kisses my forehead. His lips are warm and moist. I turn to look at him. His long curls cling to the edges of his face and tiny beads of sweat dot his chin. When he puts his arm around me, I wince and pull away. My entire body is tender with sunburn. Even my clothes make my nerve endings ache. He shrugs, then smiles, kisses my forehead again. He is somewhat contrite. I am significantly less so. When it is all over, after Brother Marcus has danced down the aisles and preached himself hoarse, after he has heard testimony from each wanting couple, after he has taken up a collection because the work of bringing about conception comes at a price, we walk back to our car slowly. We are not holding hands. “This was a mistake,” Garrison says. “I’m done with this.” I roll my eyes, open my own door, slouch in my seat as we drive away from a hope that never was. We won’t be returning.

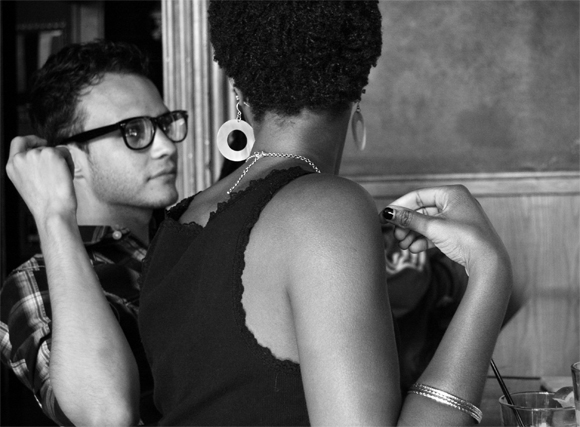

Later, in our motel room, the air-conditioning isn’t working. Our misery, we conclude, is our penance for behaving badly with one another. Sweat continues to pool between my breasts and the greasy burgers and fries we brought back to the hotel sit on a small table lukewarm and covered in congealed cheese. After rubbing me down with aloe, Garrison props open the door to our room and sits in the doorway burying his face in a full ice bucket. I sit on the edge of the bed in a tank top and panties, trying to remain as still as possible.

“This was a great idea,” Garrison says. He lowers his face deeper into the ice bucked and inhales.

I carefully cross one leg over the other and trace my thigh muscles with my fingers. I took up distance running three years ago and my legs have since become my best feature. There was no real reason for taking up a painful hobby. I simply enjoy things that make me feel bad and good at the same time. Garrison is like running for me. I pull my t-shirt off over my head and lay back on the bed even though my mother is always telling me that one should never put their bare skin on a hotel bedspread.

I turn toward the door. “Join me,” I say.

Slowly, Garrison stretches himself to his feet and with two long steps closes the distance between us. He lies next to me, kissing me, roughly, without preamble. He smells like sweat and grease and his lips are dry, creating a strange friction. His body is narrow and slick against mine, and even though everything between us is raw and humid and uncomfortable, he is pulling my panties off, working his jeans off, kneeling between my thighs as he traces through the sheen of sweat beneath my breasts. I look up at my husband. He looks completely indifferent. He’s looking past me or through me. I’m not sure which. I cover my eyes with my arm and moan softly. As he moves over and inside me, my entire body throbs. His skin abrades against mine. I wrap my arms around him as my body burns. He asks if he should stop. I tell him no, it all hurts. I lick his shoulder, swallow the bitter salt of his skin. He groans loudly. He lies. He says I love you. After he comes, he pulls his jeans back on and returns to the doorway and his bucket of water and ice. We are another place to which we will not return.

In the morning, we take the car to a mechanic, and wait for the air-conditioning to be repaired in a small waiting room that smells like motor oil and old coffee. There’s a thirteen-inch television on a small table but a clear picture only flickers through once every few minutes. I sit with my arms crossed. I look straight into the blacks of Garrison’s eyes, even when it makes me feel sick. He stares right back. We are having a standoff. We are neither willing to draw first. We are saved from making such a fateful decision when the mechanic interrupts our staring contest, wiping his hands clean. “That should get you back to where you’re going,” he says. Garrison pays for the repairs with money we don’t have and then we’re on our way.

As we pull out of Baptiste and feel cool dry air blowing over us for the first time in days, I burst into tears. The sheen of sweat covering my skin turns into goose bumps. Garrison reaches for my hand, but this time, I wave him away. I lean forward, pressing my forehead against my knees. I lace my fingers behind my head. I cry until I’m cold all over.

In a year, Garrison will have a baby boy who looks just like him. It won’t be with me. I’ll be having an affair with my boss who is married and already has four children of his own. My husband and I will run into each other while standing in line at the movie theatre or at the grocery store. Sometimes, he will be holding his baby boy in his arms. We will pretend we don’t know one another. We will be happy.

Read more about Roxane Gay here.

Read more about Timothy Paul Moore here.

another stunning piece of writing by Roxane Gay. Wonderful.

Brother Marcus interests me, and I would like to see more of that scene, but the all-consuming desire for a child seems to have been floating aimlessly around in space and happened to smack into the narrator. The extortionist priest was a final final desperate attempt at saving something beyond repair, a relationship supposedly ruined by a barren womb, but there has to be more to it than that. The narrator dismisses adoption with a “Blah blah blah.” Is it that she only wants what she can’t have? She could adopt a child, so she doesn’t want to. She has an affair with a married man because he will never be hers. The baby is a sold-out accessory that she will do anything to get her hands on, and then once she finally does, she loses interest. I would prefer a more omniscient point of view to get a glimpse inside Garrison’s head to see what this woman looks like to an outsider.

Wonderful story! so much tragedy in this relationship

Wow. A brilliant story and heart-rending. Such amazing descriptions and so much evidence that they are disconnected and broken.

“The baby is a sold-out accessory that she will do anything to get her hands on, and then once she finally does, she loses interest. I would prefer a more omniscient point of view to get a glimpse inside Garrison’s head to see what this woman looks like to an outsider.”

Melissa, the tone of your former sentence answers your latter desire. Garrison isn’t the outsider, he’s deeply inside this relationship and its needs. You – and any reader who has never known the complete broken hearted tired ache of your body, or your partner’s body, needing to produce offspring – are the outsider. No one is in the relationship but the people in the relationship.

I love this piece and I hate that I identify with it so strongly. I hate what trying to produce a child has done and is doing to my marriage.