The first time he was struck by lightning, Blankenship said, “Whoops.” One minute he was scooping pine needles and sludge out of his gutters, a deceptively blue spring day, and then the next neon-bright lightning speared out of the sky and hurled him off his ladder. “Whoops,” he said as he flew through the air, smoking like a censer. “Whoops,” he said again when he landed facedown in the pachysandras of the neighbor’s lawn. He reached to see if his head was still attached to his body and touched his bald spot, hot as a Bunsen burner. A smell of caramelized sugar and scorched brisket wafted from his armpits. He had no idea how much time passed before the paramedics loaded him into the back of the ambulance.

By the time his wife showed up at the hospital, the nurses had him bandaged and salved. “Oh, Burt,” she said. “My poor, poor Burt.” She leaned over his bed and kissed his forehead, his chin, his ears. Blankenship glanced at the doctor, embarrassed by this show of affection. She knew how he felt about such things. The nurses said it could have been much worse. He was a forty-six year old man and in no shape for getting struck by lightning. The doctor called it a miracle and his wife said God must have been looking out for him. Blankenship stayed quiet. She also knew how he felt about this.

*

The second time he was struck by lightning, Blankenship was on the golf course with his brothers, Barry and Bill. A family reunion, at least what remained of a family. Everybody else was dead or had joined some Pentecostal church in Kentucky.

They were on the ninth hole and Blankenship was in his backswing when blue lightning cracked down from the overcast sky, haloing him in light. He jigged on the grass, brain hissing like hot bacon grease, and then he collapsed. His brother Barry rushed to his side, took off his windbreaker, and draped it over his fuming body.

Bill told Blankenship that he was sorry they’d drifted so far apart over the years. Blankenship could have sworn he saw tears. Here, finally, was an opportunity for absolution, for grace, but Blankenship said nothing.

His brothers helped him into the golf cart and then sped to the clubhouse. They carried him into the dining hall and sprawled him out on one of the plush red leather booths as the maitre d called for an ambulance. Blankenship snapped out of it and said there was no way he was going to the hospital. His insurance premiums were high enough as it was and, look, not so much as a hangnail. He was fine, just fine, no reason to make a scene.

Blankenship’s brothers were older and had bullied him well into adulthood. To this day a game of one-upmanship remained between them. They were fond of comparing cars and boats and angioplasty scars. That’s why Blankenship got up from the booth and crossed the dining hall, making a point to amble, jangling the change in his pockets. He sat down at the bar and drank a gin martini while his brothers watched, already looking forward to the day when he could say, “Remember that time I was struck by lightning? The second time? I ordered a gin martini and then we finished our game like nothing happened.”

*

The third time he was struck by lightning, Blankenship was at his retirement party. Firing party, more like it. He was old, stale-brained, a widower prone to epic gaffes, and his boss McHale suggested that now was an opportune time to slow down and savor life, which meant please leave before you end up hurting someone or burning the place down.

Blankenship was beside McHale’s koy pond, near the cabana, when lightning blasted out of nowhere and struck him on the head. Black smoke billowed from his mouth and his dentures shot out like a misfired hockey puck. They shattered Mrs. McHale’s wineglass so she was left clutching the stem, cabernet splattered on her blouse. Speechless, thunderstruck, his coworkers watched. Blankenship had had nightmares about such a humiliation, and now look.

He rushed to Mrs. McHale’s side, his eyebrows smoldering like incense sticks. He grabbed a napkin and patted wine off her face. “I’m sorry,” he said. “I’m so, so sorry.” Black smoke puffed out of his mouth as Mrs. McHale waved him off.

“You poor thing,” she said. “Look at you.”

“Blankenship, sit down, man,” McHale said. “You’re charred. You’re like a briquette.”

Blankenship knew McHale was only worried about a lawsuit, but out of habit he did as he was told. He thumped down in a wicker chair, holding his hand over his gummy mouth. He spotted his dentures in the lily pads of the koy pond, wondered how he could get up and grab them without attracting attention.

“Nothing to see here, folks,” he said. “Go back to your party. Please, enjoy. ”

They were watching, muttering, shaking their heads. Someone mentioned calling a doctor, but Blankenship said he wanted to be left alone so he could regain his bearings.

He snuck into the house and through the front door, leaving his teeth behind. He got into his Renault and sped away from McHale’s mansion, thankful that he’d never have to see any of those people again.

*

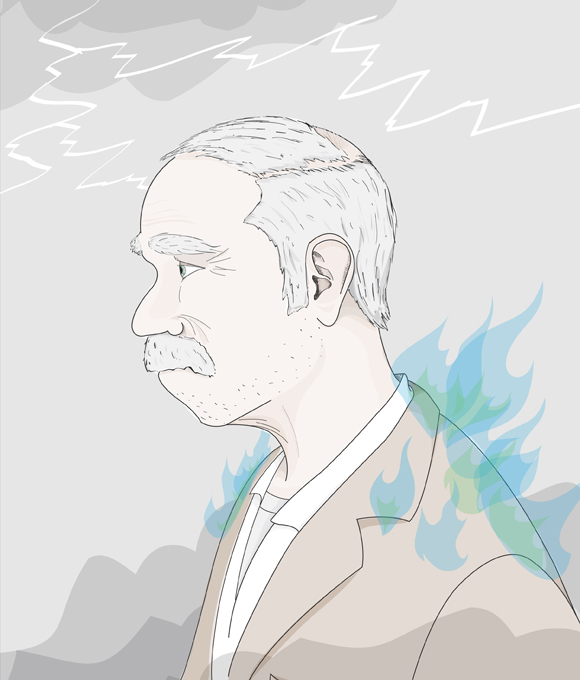

The fourth time he was struck by lightning, Blankenship was at a bus stop, on his way home from a cribbage game. He was eighty-two years old and no longer in any shape to drive. It was a dreary south Florida afternoon, almost as dark as night, but he no longer worried about the weather. He’d been struck by lightning three times, and you never read about people being struck a fourth. It just didn’t happen. The odds were in his favor. He was thinking along these lines when lightning slammed down from the pigeon-colored sky and tangled around him like barbed wire. “Whoops,” Blankenship said. His umbrella flew from his hand and crackled into flame.

There were three other people waiting for the bus, two older women and a kid with a safety pin through his eyelid. They all screamed as Blankenship glowed and sizzled and shook.

“I’m fine,” Blankenship said. “It’s happened before. No reason to worry.” His innards felt as if they were roasting. There was a sound like popcorn between his ears.

“But, honey,” said one of the women, “you’re on fire.”

He looked down and saw that he was. Epaulettes of blue-green fire flickered on the shoulders of his good gabardine coat and he slapped them out, wincing against the pain in his fingers. “Thank you,” he said. “All out.”

“Your hair too,” said the woman. “Jesus, your hair.”

“Yes, yes, thank you,” Blankenship said as he smacked his head. “It’s all over now.”

The safety pin kid was filming Blankenship with his camera phone.

“Please don’t do that,” he said. “Have some respect for people’s privacy.”

“I’m putting this shit on the internet,” the kid said.

“No you’re not,” he said. “Not unless you want to hear from a lawyer.”

The bus wheezed to a stop in front of them. The women and teenager got on board, and Blankenship followed after. He dropped his token in the box and the driver scowled. “I can’t let you on like this,” he said. “Come on.”

“I’m a citizen. A veteran. I just paid.”

“Look at your shoes,” the man said. “Look at your coat.”

He did. They were spewing peppery smoke, black and dense, and it was beginning to fill the front of the bus.

Blankenship shoved past the driver’s hairy arm and there was a lot of yelling and cringing as he swooned down the aisle, trailing smoke and heat. The gawking faces were still turned after he found a seat in back. “Please,” he said, “Go about your business. I’m fine. There’s nothing to see.”

He opened his mouth as if about to say more, one last important thing, but then he died.

Like the story? Check out our print issue.

Read more about Thomas here.

Read more about Colin here.

‘Epaulettes of blue-green fire flickered on the shoulders of his good gabardine coat and he slapped them out, wincing against the pain in his fingers’

Some of the sentences are mindblowing. The story stays true to its modest ambition. Which is the best part. And yes, it is extremely well written.

Two thimbs up!!

Quite a story. I was drawn in because I once knew a landscape contractor who’d been hit by lightning twice and claimed he felt the second strike coming based on how he remembered feeling before the first one got him.

Anyway, excellent writting!