In 1988, when she was twelve and I was nine, my cousin and I had our last sleepover. She was visiting the city because she needed an operation. Her mom had given her a kiss and closed the door to my bedroom fifteen minutes before. They always kissed hello or goodbye on the mouth. I’d never gotten used to it.

The door wasn’t quite shut so I’d gotten up to close it properly, with the click. We needed that click before we felt safe to whisper.

We’d already said goodnight. The lights were off. A few moments before brushing our teeth, staring at our reflections in the mirror, she’d told me her summer vacation was going to be stretched an extra week. They were inspecting her school for asbestos. I was so jealous I’d forgotten to rinse and had toothpaste in my mouth while I followed her into my room. I swallowed it a few times but it was still there. We both had on our pajamas. My room felt like a cookie jar with her inside it.

“The whole drive down to the city you acted like my kidney thing was contagious or something.”

“I know. I’m sorry. I know it isn’t contagious.”

“You acted like it was. You asked to sit in the front seat instead of with me. You never did that before.”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “Hospitals just give me the creeps.”

“They give me the creeps too! You know that.”

“I know. I’m sorry. I’m really sorry.”

“It’s okay. I hate always being sick. I hate sick people. You never get sick. So let’s talk about something else. What color do you think my eyes are?”

“They’re blue.”

“I know they’re blue. Did you know people with blue eyes see better in the dark? I learned that recently. I’m not really interested in the scientific mechanism behind it. I just assume it’s a mystical thing.”

“What’s mechanism mean?” I asked.

“First tell me what kinda blue my eyes are.”

“You want me to describe them?”

“Of course I do.”

“I can’t describe them. I can only compare them.”

“Okay,” she said. “Compare them.”

“I have a couple possibilities, but I can’t decide between them yet.”

“Between what?”

“They look different when you’re playing cards with Grandpa than they do when you’re talking to your sister.”

“I can’t stand my sister. She reminds me of musicals. Modern musicals.”

“She reminds me of Barbara Streisand.”

“Her dad has the physique of a slave trader. I told him that after he refused to put on a shirt while eating breakfast. It was revolting.”

“You said that to him?”

She giggled. “Do you think I’m really mean?”

“Maybe sometimes,” I smiled.

“You know, whenever you talk about me you make the same face you do when you ride a bike with no hands. It’s exactly the same face.”

“You’re one of my favorite subjects.”

Besides the circumstances of her visit, at first, there wasn’t anything special about us having a sleepover that night. By then we’d had a hundred sleepovers together. All but a handful of them consisted of me on the floor in a sleeping bag and her on the bed. She’d sleep on the edge of the mattress with her arm hanging over and I’d hold her hand and press it against my ear. She had soft hands and kept her grip even after she fell asleep. I’d only ever get fished up into bed in the middle of the night if nightmares got her. Even though she barely ever had nightmares, it was the same one every time. That’s all she would say about it.

I zipped up my sleeping bag, stared at the glow-in-the-dark stars and planets on my ceiling, and waited for her to lower her hand. When she located the coordinates of my hand in the dark she tried to pull me up. I wasn’t ready for it. She asked me what was wrong. I didn’t answer.

“I’m not sleeeeeeepy,” she moaned.

I slithered out of the sleeping bag and climbed under the covers with her. We were both on our stomachs. We’d never let go hands. Then she came over. The sounds she made sliding over the sheets had a new sound. It disturbed me. Some of the folds of our pajamas were nearly touching. I could feel it. I was really concerned about it. She let go of my hand and lay on her side and stared at me. A streetlight outside my window streaked across her face. When she leaned a little more into it her eyes looked like revolving doors. No color, just intention.

“You’re not gonna get my kidney thing. I promise.”

“I know I won’t.”

“I had a lot of nightmares lately.”

“Still the same one?”

“Yeah.”

“Can you tell me what it’s about?”

“No.”

“Nightmares aren’t contagious either, you know.”

“I dunno about that. What if they are?”

She got closer until her waist and stomach pressed against me. I could feel her new curves touching my elbow. They hadn’t been there in the Christmas photos she’d sent me. Now they were part of her. I could feel all the artifacts of my childhood in that room witnessing something.

My father and her mother were downstairs. Maybe they were outside on the porch having a drink. Nobody had ever interrupted us on a sleepover. Never.

She pried her foot between my feet and the studio audience in my brain tore out their seats.

I never saw her that often but she was the closest person to me in the world. She had a skeleton key into every door in my life. Now she’d rigged them all with explosives. Every little thing we’d shared suddenly felt wildly flammable. Even her freckles seemed sinister.

By default I let go and grabbed her hand again, like pressing reset on a Nintendo.

She discarded my hand, took hold of my wrist, and slowly began guiding my hand over her hip. Then she left it there, like a dare. I remember worrying about how anyone would remember me if I died by incestuous-induced spontaneous combustion. The off-key something that was happening had gone from a note, to a melody, to some kind of exhilarating and disturbing symphony.

“It’s just, I’m not that sleepy…”

Something strange happened when I was around eight years old that I was never able to put my finger on. I engineered a pretty lousy situation for myself. If you took all the paint colors of my personality during childhood and tossed them into a pail, an ugly hand started stirring them and everything turned black. I got sad. I stopped doing homework. I ate too much candy and got fatter than my fat cousin. I didn’t have anything nice to say and wasn’t interested in hearing about anything. I didn’t like anybody. People stopped liking me. I hated hearing my name. Whatever secrets I was trying to keep to prevent everyone from hating me, people acted as if they already knew. I hated signing my name to anything. I wanted an alibi I could never quite find for being myself. I stopped wanting to live forever, or even to a hundred.

That summer vacation, after my ninth birthday, I stalled a long time before I went up to visit my cousin. My dad ended up making me. Summer vacation was nearly over before I finally went. I didn’t want her to see what had happened to me.

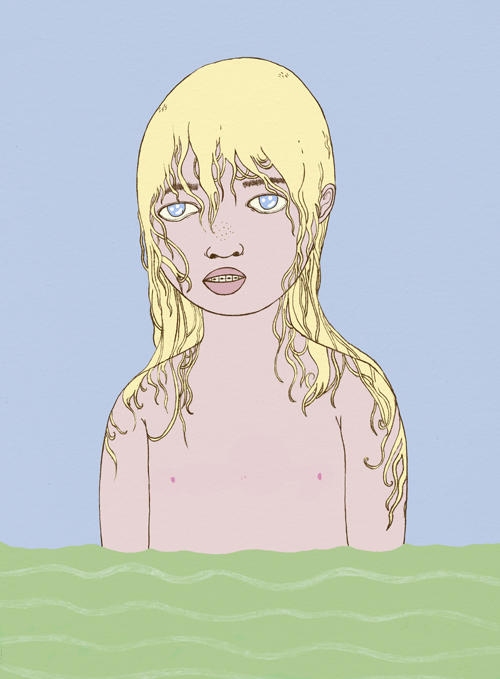

Somehow, when we pulled into her gravel driveway and she saw us through her mom’s kitchen window and started slapping the glass until it budged open so we could hear her screaming to get our attention, she seemed immune. She darted away from the window, disappeared for a split second, then exploded out the front door of her house and sprinted through sprinklers at lightning speed to greet us. Her hair flung suspended behind her, fully horizontal for two-and-half-feet, like the golden tail of a comet. I took a deep breath and got out of the car and she saw me and looked at me the way she always had. She was a little fuzzy and never quite in focus. She made me close my eyes and handed me a gift. It was an old hardcover of Alice in Wonderland. She showed me the original illustrations inside and asked if I’d read it to her.

I tried to hide it, but she could tell I wasn’t all there. She did extra things to build me up. She held my hand longer than she used to. If I got shy and let go she’d take it back again. She asked more questions and listened to me even if it took a really long time to scrape together an answer. I didn’t have a lot of answers and she was the only person who didn’t seem to mind.

That night, after the country pitch-dark spread over the sky, she took me out in the lake on their new raft. We each took a giant pole and poked at the lake bottom like we were gondoliers. It took awhile but gradually we got further and further out until the poles couldn’t find bottom. She lay down her pole, walked to one corner of the raft and picked up a homemade anchor and heaved it into the lake. She dove into the water and came back up immediately and sat on the edge of the raft. She looked over for me to sit next to her so I did.

I asked her if she was cold.

“No. I’m fine.” She slapped a mosquito on her arm. “Can I ask you something?”

“Sure.”

“Have you had a wet dream yet?”

“Ummm, no. Have you?”

“It’s different for girls. But kinda.”

“Uhhh, I found out about a guy who killed his dad in an arm wrestle though. My dad told me about it on the drive up here.”

“I read about that, too.” She’d read newspapers on her own since she was five.

She got quiet for a minute. After a while she looked over and told me about having to come back with us to the city. I asked why and she explained about an operation on her kidney. Hospitals terrified her.

Neither of us was brave.

“If I ever got in trouble would you save my life?” she asked me.

“Yeah, I think so.”

“Are you sure? What if you had to die to do it?”

“Ummm, die how?”

“What about fire or drowning.”

“Well… I think I’d be willing to die both ways to save your life. But I wouldn’t be very happy about saving you and getting burned to death. I hate getting burned.”

“But drowning would be okay?”

“If you have to die some way anyway, drowning doesn’t seem so bad. Does it?”

“In the wet dream I had I was drowning. I was in the lake holding my breath. I held it too long.”

“What were you doing?”

“Hiding so nobody could see me.”

“Why?”

“Because I was so close and it felt so good I forgot that I had to come up for air.”

The night before we drove my cousin and her mom back to the city for her operation we had a campfire by the lake. I’d brought along the book she’d given me and was practicing reading out loud.

I heard my grandfather pull up over the gravel of the driveway in his pickup truck. He wore his gray fedora and a lime-green short-sleeved buttoned-down shirt as he limped over on his bad leg. He was rolling a cigarette while he sucked on a caramel. He came over and mashed his whiskers against my face. I didn’t know it, but it was going to be the last time I’d see him outside an old-folks home. He still had his farm and his life more or less the way it’d always been. He and I walked around the grass not saying much. We stole a few things from the garden. Fruit always tasted better around him. We collected fallen willow branches for kindling while my aunt prepared marshmallows and other sweets to bring out for the fire. He lit his cigarette and smoked a puff then let it go out. Every minute or two he’d light it back up again.

He was nearly eighty and he’d only kissed one girl his whole life. His wife died the year after their fiftieth anniversary.

“Say, Wayne. Where’d those two canoes come from?”

My grandpa’s mind was going and I’d become Wayne––apparently a great-great uncle of mine who, so my dad said, bore a resemblance.

“I dunno. They aren’t from here?”

“Fat chance,” he said, limping over to inspect. “So where’s my girl at?”

My grandfather had pegged my cousin as his favorite before I was even born. They’d played a lot of cards and board games together since Grandma had died. I knew it meant a lot to him. They’d become pals. She slept over at his place all the time. She even rolled his cigarettes sometimes.

“I dunno. I came out here a while ago and I guess she’s inside. We were thinking about playing Risk tonight after dinner. Wanna play with us?”

He flicked his Zippo open and shut a few times and nodded.

“Figure I’ll see what’s cooking inside. Do me a favor and repel any Indians if they try and invade. Keep your eyes peeled.”

“Will do.”

“Okey dokey, Wayne.”

“Grandpa, do you really think that’s my name?”

He winked at me.

“Wayne, what’s that book you got under your arm?”

“Alice in Wonderland.”

“Didja know the fella who wrote that book took pictures of the real Alice naked?”

“No he didn’t.”

As he went inside my aunt’s place, my other cousin came out, the chubby one. She had a huge bag of potato chips and trudged over. I looked for a place to hide but she’d seen me.

“Hey, Brinny. Do you wanna see something?”

“Actually, I’m kinda busy gathering kindling.”

“That looks like a big enough pile already.”

“I have to get more. A lot more.”

“I gotta show you something. Trust me. It’s worth it.”

“Whadja mean?”

“Did you see those canoes?”

“Grandpa just mentioned them.”

“I’ll show you why those guys with canoes came over here. But we have to be quiet. Really quiet.”

“Where are they?”

“They’re in the barn. So we have to sneak up on them.”

“What are they doing?”

“You’ll see.”

To avoid the gravel we circled the house counter-clockwise and went around back over the grass. Over the nightsong of the crickets and frogs we could hear the freezer humming inside the shed. We hid behind it and peeked around the corner at the barn. Past the barn, at the other end of his property, Fast Eddie was silhouetted against his farm in a hammock, smoking a cigarette. It was too dark to see the flooding but you could almost feel the smothering weight of it over his crops. Mosquitoes were hatching in there by the millions and bats were out hunting them, making clicking noises. A shotgun went off somewhere in the valley. Coyotes in the hills sang a few bars about it. In a couple hours the rednecks would start drag racing on the highway.

“Let’s get on our stomachs so nobody hears us. We really don’t wanna get caught.”

“Neither does she.”

“Huh?”

“Yeah, let’s get down.”

We got down low, I took the lead, and we started crawling towards the entrance of the barn. It was so dark I couldn’t see my hands in front of my face, but the moonlight traced the outline of the barn. I knew more or less where the entrance was. We crawled over pebbles and puddles. Peacocks shouted at us from their cage. I kept moving closer waiting to hear a sound inside the barn. Nothing.

Someone tugged at my shirt.

“My dress is all wet. I’m going back.”

“No you’re not.”

“I have to.”

“Wait for me. I’m gonna keep going. Just wait here.”

“Okay.”

I wasn’t far from the entrance to the barn. I could smell cigarettes. I moved over the dirt more cautiously. Only the toes of my sneakers touched the ground. I heard a zipper echo inside the barn and stopped cold. A car’s ignition ground suddenly and headlights beamed straight at me for a second then cut out. The headlights had penetrated into the barn. I’d seen a row of people standing and one crouched down beside them but I couldn’t tell what they were doing. The people standing were facing me but I wasn’t sure if they’d seen me. The one crouching was facing them with their back to me. I heard men’s voices and heavy, steel-toed creaking steps. A flashlight flicked on from inside the barn and I jumped up. Then I was caught in it. The car’s engine turned again and I was trapped in the crossfire of their lights too. I turned and ran. My little cousin got up and ran straight for the grapevines while I tore off for the house.

I booked it across the dirt and over the grass toward that front door. A flashlight was combing around for me but not much of it was getting through a hedge. I was running so hard I crashed into my aunt’s crab apple tree but so much blood was pumping I bounced back up and kept going toward the dim blinking lights of a TV leaking out a window. Cement was under my sneakers. I jammed my thumb against the button on the handle and ripped open the first door. I turned the knob of the second and locked it behind me.

My heart was pounding so bad I thought I was going to puke. Nobody was watching the TV in the living room. I ran over to the window and saw the grownups around the campfire by the lake. I could see my dad’s face in the firelight. I knocked over some framed photos on the ledge. One of them was cracked. I wasn’t sure if I’d done it. While I was putting them back up I saw more family photos hanging off the walls in the window’s reflection.

I raced over to the hallway closet and stole a blanket and a pillow and threw them on the couch. They had a huge pile of videos tossed into a giant basket beside the TV and I mashed around the tapes until I found what I was looking for and slipped it into the VCR. A second later I was back on the couch drowned in covers. I reached down behind the cushion into the cookie-crumbed and spidery bowels of the couch until I got hold of the remote. I pressed play and Richard Gere was ordering strawberries from room service for Julia Roberts. I turned my back to it and stuffed my face as deep into the crook as I could, pressed up hard against the spring.

* * *

While I was in bed with my cousin back in the city the following night I couldn’t stop thinking about that barn.

“Are you sleepy, Brinny?”

“No,” I said. “Last night at your mom’s, she told some guy that I slow-motion the nude scenes in Pretty Woman.”

“There aren’t any nude scenes in Pretty Woman. Julia Roberts wouldn’t do any.”

“I know.”

“Just the way she is.”

“But she already told the guy I’d seen it a thousand times. Isn’t that bad enough? Why would she need to lie about the nude scenes to embarrass me?”

“Why did you sleep on the couch instead of in my room?”

“Is it okay my hand’s still there?”

“Why wouldn’t it be?”

“Were you in that barn?” I asked.

“Maybe.”

“With those guys?”

“Possibly.”

“What were you doing with them?”

“Umm…”

“Are you still a virgin?”

“Have you kissed a girl yet?”

I shook my head.

“Would you like to?”

“Are you still a virgin?”

“Are you jealous of those guys?”

“Were you having sex with them?”

“You can move your hand now if you want.”

“You’re uncomfortable?”

“No,” she said. “That’s not what I mean. You can move it around if you want to.”

“Where?”

“That depends. Where would you like to move it?”

We heard the front door slam downstairs and someone climbing the stairs. I bounced off the bed and jammed myself into my sleeping bag. The door opened. Lights went on. I squeezed my eyes closed as hard as I could. We heard my aunt’s voice:

“Tonight you’re going to sleep downstairs.”

“What’s the problem?”

“Is he asleep?”

“Yeah.”

“Let’s go.”

“Why? I feel like I’m under house arrest or something, mom.”

“We’re not discussing this.”

“You’ve never done this before.”

“Now I am.”

After my cousin climbed out of bed and followed my aunt out of the room and started down the stairs, she came back and closed the door with the click. I heard my aunt’s voice behind her but I couldn’t hear what she was saying. The door opened and my aunt came into the room holding something that she placed on my nightstand. She looked over at me.

“Oh, you’re awake,” she said. “You forgot Alice in Wonderland at my place. Goodnight, Brin.”

After she let herself out, I climbed into my bed and lay there staring up at the glow-in-the-dark planets and stars on my ceiling for a minute waiting for my cousin to find a way back into the room. I leaned over and smelled her pillow. I looked over at that book on my nightstand. I got up and grabbed the book and walked over to the door to close it with the click. I stood there and waited another minute for her. It was really stuffy in my room so I went over to the window and tried to pry it open even though it was painted shut. I put the book down on the window ledge and kept trying but I couldn’t make it budge. Finally I gave up. I grabbed the book off the ledge, wound up, and threw the book as hard as I could at the glass and watched it all sail down onto the hood of a parked car in the street.

I went back over to my bed and took her pillow and peeled off the blanket and brought them with me to sleep under the bed.

Like the story? Check out our print issue.

Read more about Brin here.

Read more about Donya here.

Dangerous territory navigated elegantly. The characters are beautifully drawn, and moving. The evocative settings were pure bonus. Love this piece.

I found it interesting how you left out that asbestos was a/the major contributing factor in what killed Lewis Carrol. Very creepy how in his letters Carrol praises the miracle of asbestos with his fireplace while, obviously, it’s clandestinely destroying his lungs. Eerie metaphor in this context of a girl’s sexuality.

Brin,

Greatly enjoyed Asbestos! Love the title: evocative metaphor for a slow poisoning. Fine, brave writing. The shattering of a child’s illusion of love/purity in a beloved is so well handled here in edgy terrain that I say, Bravo.

Best,

Lucinda