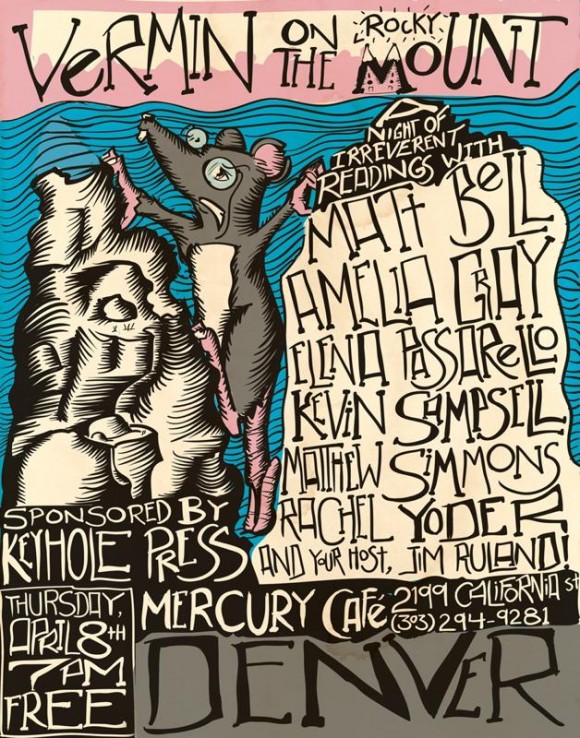

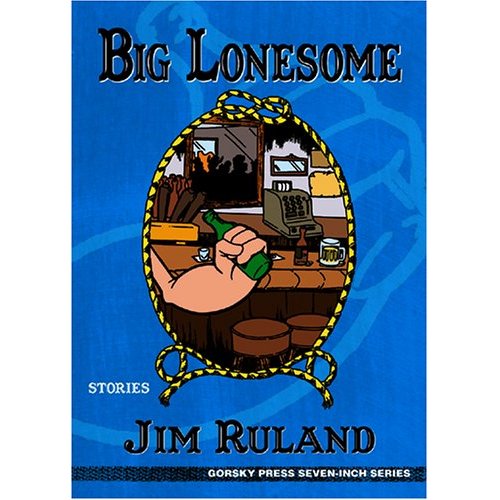

Issue Six contributor, Jim Ruland is the author of the short story collection, Big Lonesome, and curator of Vermin on the Mount, a reading series hosted monthly in LA. We spoke over the phone last week concerning writing, work and the Navy.

A: So we had to postpone this cause you were at work?

JR: Yeah, I was at work, and the big pacific west coast time difference thing.

A: So where exactly do you work?

JR: I work at an Indian casino.

A: So what was happening? You guys were doing an installation or something?

JR: Yeah we were putting together something for a new promotion. It involved a bunch of graphics down on the floor.

A: What kind of work do you do at the casino?

JR: I’m a copywriter. I write all the ads. Do all the copywriting for the marketing department.

A: Do you get any inspiration for stories from your work?

JR: I do. I got a novel out of it. It’s kind of a mingling of my sordid past with on-the-job details.

A: What about from past jobs, not necessarily from your current one, do you take a lot of inspiration from job stories?

JR: I wouldn’t say a lot. Lately I have been. I haven’t worked all that many jobs, and I haven’t written too much about my experiences in the Navy. I certainly haven’t written anything about teaching. Advertising presents plenty of opportunities, different things to draw on. So I guess I have.

A: I read that you were in the Navy, but most of the stuff that I’ve read of yours doesn’t really reflect that. Do you feel like the Navy had any influence on you at all?

JR: Oh yes. It was a huge, huge influence for sure. I went to a private school. I thought the world owed me something. But the Navy very quickly disabused me of that notion. It was a really great experience. It was also a really terrible experience in the sense that it’s a pretty instantaneous loss of innocence. And that has nothing to do with wartime/peacetime, it’s just from being around a bunch of sailors 24/7. I imagine it’s the same in the Army or the Marines. Just living on a ship, going out to sea, spending a lot of time with people in the service, you get a pretty different view of things pretty quickly. It’s definitely what every 18-year-old needs.

A: Why the Navy?

JR: Because my dad was a naval officer and I needed to prove that I wasn’t like him. Little sarcasm there.

A: What kind of private school did you go to?

JR: Catholic school. Went to a catholic school in the suburbs of D.C. There were about 400 people in my class and I think I was one of about five that didn’t go on to college immediately after high school.

A: When did you move out to the West Coast?

JR: The navy stationed me. I enlisted and I got sent out to San Diego. A place I hated and swore I’d never go back to. And now here I am again 20 years later. I don’t know why I hated it then. It’s beautiful here. Maybe I didn’t like beautiful things.

A: Did you start writing when you were in the Navy?

JR: No, that would have been a recipe for ridicule. I didn’t start writing until college. Incidentally, I wrote my first essay about helicopter duty on the frigate I was stationed on. My teacher loved it. Maybe because it wasn’t a cancer story or a grandparent dying story or a losing virginity story like so many people who teach composition get to read.

But his response to my essay and the idea that someone would be interested in something I wrote was a huge inspiration.

A: How old were you then?

JR: About 20 I imagine.

A: Was this the turning point when you were like, “I wanna be a writer”?

JR: I had ideas of being a writer but it was just that. It was just kind of a romantic idea. And I was always a big reader. And that didn’t slow down at all in the Navy cause I got in a lot of trouble so I had a lot of time on my hands when I wasn’t allowed to leave the ship. I’d just read. There were different things that made me interested in writing, but after spending some time in the fleet, with people telling me what a stupid fuck-up I was, I began to believe it. So that kind of quashed any notion that I could be a writer.

But there was a writer in my family. So I guess it was always in the back of my mind. It’s kind of like, when someone you know is a singer or an actor or an athlete or whatever, there’s always that awareness of it as a real possibility. I guess it’s the same with firemen and cops. You see someone work at it and ultimately succeed at it and that makes it real for you.

A: Who was the writer in your family?

JR: I had a cousin who was a screenwriter. Mark Patrick Carducci. He passed away almost 13 years ago. He was an inspiring person in my life, because he worked so hard. His passion was horror, monster movies. And it was something he took a lot of shit for, frankly. People thought it was a phase he would grow out of, but it was what he really loved. No one could talk him out of it. I understood it wasn’t something to be talked out of. It was his passion, it was what he wanted to do.

He stuck with it and wrote a bunch of movies. Probably the one that most people are familiar with is Pumpkinhead.

A: No shit! I remember seeing the box for that whenever I would go to the video store with my parents and I remember it always scared the shit out of me.

JR: He wasn’t really a slasher horror kind of guy. He was into moral horror. “The things you do on this earth matter” kind of thing. So the slutty chick, she’s gonna die. The douchebag, he’s gonna die. They’re kind of rewarding to watch in that way because that kind of behavior, you don’t see it get punished anymore. Now the douchebag and the slut get their own reality show.

A: (laughter) They don’t get punished in literary fiction either.

JR: No. Well, that’s hard to say. It’s an old fashioned way of thinking. Maybe in Cormac McCarthy novels they get punished. Eventually.

But he wrote a lot of interesting things. He wrote Neon Maniacs. He did an episode of “Tales of the Darkside.” He was very busy. He wrote and filmed a documentary about Ed Wood that came out a couple years before the Johnny Depp film came out. It was called Flying Saucers Over Hollywood: The Plan 9 Companion. He was a very influential person in my life in the sense that I always also had unconventional tastes, whether in fiction or in movies. And his example has been one that has always encouraged me. He killed himself thirteen years ago. I miss him.

A: I wanted to talk a little about “Fight Songs.” What was the original title?

JR: It changed. Sometimes I’ll change the title just to change its luck. And now I kinda do it compulsively. I think it had a couple of titles. But they were all really long. “Our Lady of Perpetual Sorrow Needs a New Fight Song,” was one.

A: So I take it you weren’t upset that we had to change it.

JR: No. I was at a fiction workshop at a conference in Utah and Thomas Mallon gave the advice, “When dealing with editors, never change your title because they know if you change your title, you’ll change anything.” Which is really good advice, but it just so happens that titles are titles. Sometimes it can work against you to get too attached to things. And the other thing was I’ve been in advertising so long, you write a piece of copy you get input from twelve different places for twelve different reasons, and you just have to go back and do it again. It doesn’t mean the copy is wrong or the copy is bad, it just means the right set of circumstances hasn’t lined up where you hit the target. And I think that’s something that, when you’re working with a literary magazine, you’re not just working with an editor, but a whole slew of people. I think you told me it was a design problem, that the title was too long.

A: Yeah, it wasn’t fitting in the table of contents. We had everything in a center column and it was sticking way far into the gutter so my designer was like, “You gotta tell him to change it because we just can’t make it fit.”

JR: I think writers sometimes forget. If you’re interested in publishing, then the precious little thing you do at your desk becomes a collaboration. You gotta be flexible.

A: Where did this story originate?

JR: Boy, I don’t really remember. I lived in Playa Del Ray, where the story ends, for about five years. It has a really interesting history in that it was one of these failed resort places. And it had this whole pleasure palace and this kind of weird lagoon where they did boat races. If Venice Beach was supposed to be the next Venice, Italy, then Playa Del Ray was supposed to be the next Coney Island. But it was right at the mouth of the LA river, which before the corps of engineers took a whack at it, flooded regularly. So that whole resort area got wiped out. There was a film studio there. The company that made the Keystone Cops movies set up camp there and eventually moved on. It was kind of like a bust town. And a lot of the streets are named after people who tried to develop it. Kind of interesting in that way. But none of that’s in the story.

A: (laughs) I initially liked the story because of the voice of the narrator and the character of his girlfriend’s daughter. They seemed very real to me of the first read. How do you go about writing characters?

JR: I tend to be more about situation. You hear a lot of people talk about voice, but I’m always interested in what makes a good story. When you read a newspaper, you’re like “Oh, this is something interesting” and it’s usually not because of a person, it’s because of something that happened and I think that’s just where my interest is. So I start there.

I worked at an advertising agency in L.A. for a number of years and moved around to a couple different offices. I really did move into someone’s (old) office and find all of their stuff, just like in the story. But I didn’t find a secret blog, much to my disappointment. But I was kind of surprised that the person would leave so much personal data on their computer. And that person didn’t get fired. They just left. I was surprised the company would be like “Okay, here’s an office open with all this stuff in it, just go right ahead and take it, it’s all yours.”

Around the time I was writing the story, I was dating someone who had a daughter around the same age as Jessie. But that relationship ended badly and took a long time to end. So I did everything I could to make those characters not like the people that anyone who knew me might assume they were based on. If that makes any sense.

A: Why did you intentionally not make them like those people?

JR: There was enough drama as it is. I didn’t need to manufacture more. And I certainly didn’t want my ex to think that I was writing about or inventing scenarios with her daughter, which I certainly wasn’t. But that tension was always there in the story. I guess I was overly concerned with people getting the wrong idea. As the story took on a life of its own and the years passed, and then more years passed, it became harder to remember all the details about them and then move in the opposite direction. The characters just moved where they wanted to go, and I fought it in every draft. Maybe that’s why it took it so long to get published. Anyway, once I finally relented and let the story go where it wanted to go, then it felt true and I was able to trim off everything that didn’t belong.

A: How many years were you actually working on the story?

JR: It was a long time. Five maybe? After Big Lonesome came out in 2005, I was more interested in long-form fiction. Various novel projects I was working on. And then there was all these other extra curricular things that got in the way on and off over the years. So I was only writing a couple stories a year. So because I wasn’t really invested in writing short stories, I wasn’t sending them out as earnestly. But I think (Fight Songs) still probably racked up 20 or 25 rejections.

A: Let’s talk about “Big Lonesome.” I was really surprised by stories like “A Terrible Thing in a Place Like This” and “Red Cap” by how incredibly dark they were. They betray this kind of lighthearted swagger that I’d come to associate with your style. Do you search for that sort of balance between light and dark in your writing?

JR: When I wrote those stories I didn’t write them with a book in mind. I wrote the stories that I was interested in. I wasn’t thinking about a reader. Now I most certainly think about that balance, especially the swagger and the light heartedness. I still think I go to some pretty dark places. I’m thinking of the novel I’m working on now. But I think more than ever I’m focused on humor, or the possibility of humor.

A: How do you pursue that humor? Because I think it’s really hard to be funny unless you actually are funny. I find it hard to try to be funny. I find that humor just sort of happens and you’re not even really aware of it.

JR: It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy in some respect. It’s like Kafka’s bug. You wake up and you think you’re a bug and believe you’re a bug then you’re a bug. If you believe that what you’re writing is funny then it is. I think that’s the swagger that you’re talking about.

It does surprise me how few novels are funny. I just finished James Greer’s The Failure last week and it’s hilarious. It’s funny in the same way that Sam Lipsyte and Jack Pendarvis and Patrick Dewitt are funny. Dark and bleak kind of humor. But then I look back as I’m preparing for a reading, I have very few relatively funny pieces and a lot of really dark ones. So, go figure.

A: I laughed out loud on some of these stories. Like “Kessler Has No Lucky Pants” like the back and forth that was going on there. I think it was Sam Lipsyte who was talking about dialogue and he said it’s like a push and a pull. And I saw that in that story and thought it was really effective.

JR: That device, everyone calls it a Q&A, but it’s really a catechism. I just ripped it off. And Joyce used it to great comic effect in the penultimate chapter of Ulysses. He’s a lot funnier than I am. I don’t think a lot of people associate Joyce with humor, but he’s extremely funny, and Ulysses is, essentially, a comic novel. So that’s where I got the device from. And the great thing about that story is that at readings anybody can read the questions, and they can do it in any particular style. They can ham it up or they can be serious or they can be stumbling drunk and it really doesn’t matter. When I was touring I would get a member of the audience to read the questions, and it seemed to go over really well.

A: There are a lot of good aphorisms in BL, especially in “The Eggman.” What inspired that style of dropping profound knowledge in a story?

JR: Wasting a lot of time and money in bars.

A: (laughs)

JR: That’s usually where you hear those kinds of things. That barroom wisdom. Good for a chuckle and works in the dark but probably not a good idea to carry it around with you in the screaming light of day.

It was definitely a time in my life when, not only did I spend too much time, but I aspired to spend more. So maybe something good came out of it.

You know how it is. You’re in a bar and you’re by yourself, but a drunk will sniff you out. He or she will say something funny in the first minute or two. They’ll make you laugh, so you let your guard down, invite them in. And then they just make you miserable for the next hour or two.

A: (laughs)

JR: And then they’re talking you into going to buy some bad crank and then your life is ruined forever. All over some supposedly hilarious joke they told you.

That story came out of a road trip I took when I was in grad school to a conference in Albuquerque. I drove with a bunch of friends from Flagstaff. And when I got on the campus there were some protestors or some kind of demonstration and someone gave me this flower. I carried this flower with me for the rest of the day, all through the night. I was just struck by how differently people talked to me because I had this ridiculous flower.

I remembered that when I was creating the situation for the character with the egg, having to carry it around, which I guess is a real anger management tactic. It teaches you empathy. To care for something fragile. Or some horse shit like that.

A: What’s the fascination with these pre-existing characters like Popeye and Dick Tracy?

JR: I’ve always been interested in the history of things. Origins of things. Popeye was an endlessly fascinating figure to research and read about. Dick Tracy too. It’s fun to write about things that people bring a lot of knowledge to it. So much of the heavy lifting has been done. You don’t have to describe Dick Tracy or Popeye. As soon as you do you can introduce some irony or humor or spin it in a different direction. When people bring something to the story, you can work against there expectations. I’m doing that a lot now with the novel I’m working on now.

I’ve always been a fan of trash literature. Crime novels, science fiction, comic books. I don’t think I really got into spaghetti westerns until I was in my 30’s. I imagine my interest in these things will always come and go. I’ve got this epic war story involving sea monkeys that I’ve been writing forever.

A: Lastly, if there’s anything you can tell me about the novel you’ve been mentioning…

JR: It’s somewhat autobiographical, an autobiographical ghost story. One of the main characters finds himself in this remote place and is haunted by the life he left in Los Angeles. He goes to work every day and gets into a bad routine involving drugs and alcohol. He’s haunted by what he left behind and haunted by this need that undermines his best intentions. And like myself and like the main character in Fight Songs, he’s a copywriter. In many ways I guess the character in Fight Songs is a prototype for the one I’m working on now.

A: Is this your first novel?

JR: No. If I publish it, it’ll be my first published novel. This is my fourth one I’ve written.

A: Have you tried to get the other three published?

JR: Try is a really… uh, yes.

(both laugh)

JR: They’re kinda in the drawer. I think I need to go back to them, spend some time with them. The first one I have no interest in ever thinking about again. The second one could use some re-imagining. And the third one is pretty close and I’ll probably go back to very soon.

A: I’m always fascinated by the amount of writing that a writer does but doesn’t necessarily get published. It seems like a very 10% to 90% ratio.

JR: Yeah, but the great thing is, I wrote it. No one can take it away from me. It’s ink on a page. You could come over to my house and read it. My daughter can read it 10 or 20 years from now. We can have a conversation about it. There’s nothing theoretical or abstract about it. We’re so lucky in the sense that we’re not struggling singer-songwriters or comedians or actors. What if you had your best moment, your finest hour, at an audition for a dandruff commercial?

A: (laughs)

JR: That would be a pretty hard thing to live with. What we do is still on the page. It’s all right there.

Click here to read more about Jim Ruland.