The office has a serious problem: the office girl has taken off her shoes.

–I am so very bored, she says.

–I am also so very bored, you also say, from the cubicle beside hers.

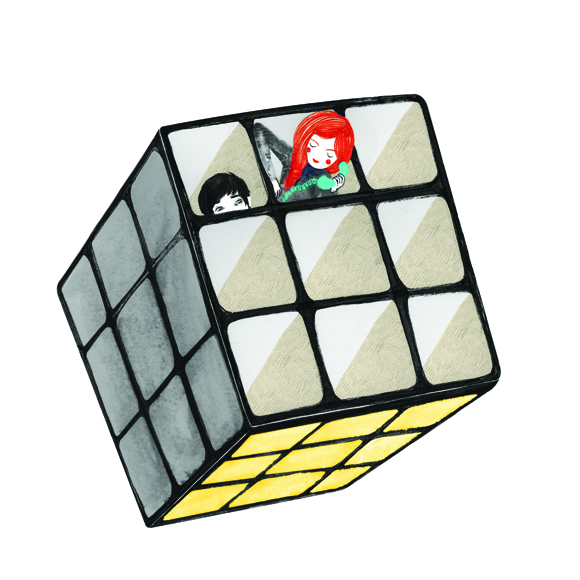

The office girl is named Odile. You learned it at orientation. You are in cubicle seven. She is in cubicle eight. Her red hair hardly gets noticed because all of the other office workers are gone by this time of night. You notice it however. You have noticed it for the last four months. It has been four months exactly.

–We should dance, she says to you. Right now. We really should.

–No, we shouldn’t, you say, trying to think of the last time you danced with anybody. You can’t, you really can’t remember ever dancing with anyone. Honestly.

The office girl and you are the only third-shift phone operators for a very small novelty music company which produces muzak anthologies of various pop songs, the kind that are often advertised on television very late at night. “It is an Acceptable Time for Midnight Romance” is one of their albums, as is “Quiet Moments For Awkward Lovers like You and Me,” which features many, many numbers by instrumental artists imitating modern pop songs. It is your job to answer the wondrous questions these poor somnambulists have as they order, questions like, Do you know much I love that song? Do you?

–I do not, is how Odille always replies. You hear her say that and always smile.

The office girl leaves her shoes under her desk and stands suddenly. Her shoes are small and white. They look like they must have been bought on sale. She only works part-time and wears the shoes of someone who may be a dreamer. Odille stretches her long legs. On the office stereo, a muzak version of some song you recognize begins playing, though you are not sure what song it is exactly. The song sounds like a real song being held against its will, under water. Barefoot, Odille strolls over to your cubicle. You are drawing a picture of your own hand, so great is your own boredom. Your hair is dark and your eyes are unconvincing. Your short sleeve shirt and black tie are both stained with coffee. You have been known, at work here late in the evening, to take off your shoes and switch the left and right one, walking to the water cooler like an untrained circus performer.

The office girl suddenly bows. You stand and bow back. You begin dancing to the music, telling yourself it is only a joke.

Ha, ha.

Look at the joke.

It is too lovely to be a joke, though, and you both know it. The two of you are as clumsy as costumed animals on stilts, but in the most charming way ever. The office lights know it is the best thing they will see sitting up there and blink sadly in approval. Everything, including the ringing phones, is soon ignored. For the office girl, Odille, this moment is just something crazy to do to pass the time. For you, it is not so funny at all. When the office girl has her head against your shoulder, you glimpse several small red freckles along the back of her neck, mysterious spots, whose existence you have been previously ignorant of. You immediately begin to buckle. You are holding the office girl’s hand in the very near dark, no music but the fake muzak arrangement of someone else’s song, just the soft step of your four shoes on the carpet, one after the other. It is a secret, this moment, and the fact that is a secret is what makes it both so dangerous and so lovely.

It is a moment where a fuss is made somewhere in your heart: though, for some reason, the glow of it does not fade.

When the office girl finishes dancing with you, you suddenly realize it has been a muzak version of a Tina Turner song that has been playing.

At the moment, Odille’s white face is flush and you are imagining kissing her right there. But you do not. It is because you have the worst sense of timing of anyone in the known universe, including members of ancient civilizations who had no concept of time at all. You are the worst where any kind of spontaneous courage is concerned. Example: falling in love for the first time in fifth grade, you spent all summer trying to get the wording right in a poem you had written to give to a dark-haired girl, and when you finally did get up the nerve, you delivered it her mailbox and found she had mysteriously moved away. You are a coward at heart, like everyone else. Finally letting go of the office girl’s hand, you make this heady realization yet once again.

It is an in, though, maybe, this dancing together, you think. The next night, around eleven o’ clock, you approach the office girl, Odille’s cubicle. The girl is eating takeout Chinese from a white carton. She sets down the white carton. You imagine describing this moment to a friend many years from now, the moment where you are now taking her hand to dance. You are recently thirty. Besides her hand in your hand, you have almost nothing else to show for yourself.

It is what the two of you do every night then, again, partly as a joke, partly because you have been thinking of the office girl, Odille, for many months now. Usually just past midnight, only halfway through your shift, the two of you will dance regularly to the muzak version of songs by popular artists you both barely recognize. You will laugh and ignore the phones and hide your enchantment by pretending it is only silly.

How you dance is like this: your arms tucked close, almost like a chicken. You do not want to seem serious about what you are doing because you cannot dance. You make sure to smile and do a crazy move, like the scuba diver or car wash or shopping cart whenever she is looking so she doesn’t think you think you are very good or anything.

How Odille dances: like all girls, she is effortless, supine, mesmerizing. She does so very little, sometimes holding her hands above her head, sometimes turning around. You see the whole shape of her and want to kneel. You know this is the great leveler, the great unfairness. You cannot walk away and reason yourself out of this.

Problems soon begin occurring at work however. Issues concerning looks which wander just past the water cooler into soft hazy spots at the back of the office girl’s unknowing neck, around her bare knees and along the hem of her soft, fluttering skirts. Ideas have begun to make themselves known. Ideas concerning inappropriate, unprofessional, and imagined kisses between members of the customer service department who were previously thought to be only work-related acquaintances, and near strangers at that. Rumors begin to circulate. You mistakenly tell Amanda in accounting about the “dancing,” honestly only wanting a female perspective about what Odille may be thinking. Amanda is less than helpful. She will share your secret and every secret she has ever been told because she wants to be liked by people. This gossipy nature is her fatal flaw and you become aware of it much too late.

What Amanda in accounting says is this:

“Big deal, you dance with her at night.” She is saying it loud, standing beside the water cooler. “You could be doing a lot of other things, couldn’t you?”

You are not sure. You would like to be. But you do not think the office girl would want to do much of anything else with you.

What will you do now is the real question, isn’t? Of course, you need the job as bad as does the office girl, Odille, so you decide you must stop dancing together. Nothing good can come of it. It will be embarrassing for the both of you if you let your feelings be known and she does not reciprocate in any way. Why would she reciprocate? She is tall. She is lovely. She dances with you out of pity. You must avoid looking bad. You must act right away before you are humiliated. This is how you avoid disappointment in your life. This is precisely why you have been alone for some time and decided to work evenings when asked.

You decide to tell Odille the very next night. The two of you are in the break room just before your shift starts. You are staring at each other suspiciously. You begin to talk first.

“Um, are you working tonight?” you ask.

“Like you don’t know already,” she says.

“I guess,” you say.

“We all know what’s going on here. You don’t have to be weird about it.”

“What is going on here?” you ask, smiling.

“I am not going to even dignify that with a response.”

You are encouraged for some reason. Perhaps, well, no, but, maybe, maybe she is interested in

you. You say:

“Are you going to order something to eat tonight?”

“Yes.”

“Well, let me know. I’ll order something, too.”

“Fine,” she says, still glancing over the top of eyeglasses at you. “But I’m paying for my own.We’re not going steady or anything.”

“OK,” you say, disappointed at what she has said, but not disappointed enough to tell her what you had planned on telling her. Immediately, you catch yourself staring. You catch yourself memorizing the shape of her eyes. You watch her get up and leave the break room and then ask the cloud of air where she has been sitting why it is so lovely.

About you: well, there is not really much to mention. Your record collection is the same as it was in seventh grade: mostly The Who, which was donated to you by your older brother when he joined the drama club and got the lead roll in “Godspell.” You are a young man who must wear a tie to work every day. Yes, you are one of those types. Your secret: you have two houseplants which you maintain very seriously as if you are somehow being tested by somebody.

About Odille: her real name is Alice but she began using her middle name in seventh grade when some someone made a comment about her real name at a slumber party, saying it sounded like an old lady’s name. The name “Odille” comes from her grandmother and is French. The fact that she now has a name most people have never heard of is not troubling to her in the least.

As soon as the cleaning ladies leave that evening, the office girl, Odille sitting in her office chair, wheels over to your cubicle.

“We are not going to have sex,” she tells you. “I want to tell you that right now.”

“I know that,” you say, though you had hoped you would and so you think that maybe she is perhaps trying to trick you. You would be alarmed if you knew how close you were to the actual truth. “Why would you even say that?” you ask.

“Because someone stole a picture of me in a bikini from the employee bulletin board and also, I know that look you have. I know what you are thinking.”

This is all true as:

1. You have indeed stolen the picture of her on the beach. It was hanging on the employee bulletin board and showed Odille on a beach in Belize, holding a white conch shell above her head. The way the sun shines in the photo makes her white face look like she is glowing.

2. As she says, you do have “that look.” The look is that of someone having feelings for someone who cannot possibly, ever, be interested back.

3. Considering each of these accusations, she does know exactly what you are thinking.

“We are two adults,” you say quickly. “I am only here to work. I won’t bother you anymore or anything.”

“Fine,” she says.

“Fine,” you repeat.

“We are too good of friends anyways,” she says suddenly, though you both know this is a lie. “We are too much alike.” Again this another very obvious lie as you really don’t know each other all that well at all. In fact, you do not have the slightest clue as to where she lives, how old she is exactly, or what might be her last name. Still, seeing this as a chance to avoid humiliation, you say:

“Yes, it would be too weird. If things didn’t work out.”

“These things never work out,” she says.

“Exactly,” you say.

“Exactly.”

Both of your noses twitch as you look at each other. The strap of her dress sighs. Almost immediately, you begin kissing. The two of you fall against the white office cubicle wall and kiss and kiss and kiss like amused, spoiled children. It is a very good, a very productive kiss.

You soon realize, however, the office girl has stopped kissing and so you open your eyes.

“I bet you have been planning this,” she whispers, stepping back, accusing you of something.

“I didn’t plan anything,” you say, which is both the truth and which is not the truth.

“I’m sure you’ll tell everyone how hot it was now, won’t you?”

“We just kissed. And it wasn’t all that hot,” you say.

“It was hot,” she says. “It was hot and now you’re going to write me up in the bathroom or whatever you infants do.”

“Forget it,” you say. “Let’s just forget this and not even talk about it.”

“I’m going home,” the office girl says. “I can’t believe I ever thought you were nice.”

The office is soon empty as you watch her step into the elevator. She has on a white winter jacket with a furry hood. As the doors close, she flips you off and you stand there in front of the elevators for almost an hour, not knowing what to think or do.

“We will stop dancing together,” you say to her immediately, the next evening. “How is that?”

The office girl says. “I was going to invite you to come home with me after work tonight.”

“You were?” you ask.

“Yes,” she says.

“But why?” you ask.

“Because I don’t have any other prospects in this lousy city.”

The apartment, her apartment, is both surprising to you and very sad: it is small, one room, a studio, the walls mostly bare. There are two white ballerina shoes hanging on a doorknob. She locks the door and undoes her hair. You both begin to undress. You try to watch her while you, at the same time, attempt to cover yourself. You both hurry beneath the covers. You hope she does not think you are too hairy. You hope your hips do not make that noise tonight. You are both under the white sheets and she says suddenly, “Once I fall for someone,” but does not finish the sentence. You start to kiss and are immediately startled by how soft her skin is.

On your walk to the bus stop, leaving her apartment the following morning, a black dog with two white spots chases you all the way up the street. At the bus stop, the animal simply keeps on running, while you fumble, glad you did not have to stab the animal with your keys.

The two of you do not dance the following night. The two of you sit in your cubicles, each waiting for the other to make the first move. It is midnight before the office girl concedes. When she does, she charges into your cubicle very angry.

“I am not going to play these goddamn games with you,” she shouts and you notice she is smoking.

“OK,” you say.

“OK,” she says and stomps back to her cubicle.

You stare at where she has just been standing. You do not speak to her or anyone else the rest of the evening.

On the bus ride home, looking out the drafty windows, you see the office girl in her pink skirt riding her bike towards her apartment. A moment later she crashes into a parked car and begins shouting. You feel embarrassed and guilty having seen it and know you are somehow to blame for the way she is standing there in the street screaming.

You want to know what the office girl is thinking and so, the next evening, you say:

“I think I made a mistake.”

“So do I,” the office girl says. At the moment, she is blowing a gigantic pink bubble, the gum like a unquestionable kiss puckering from her mouth. You want to pop it and go back and ask her if you can start over or something. But you do not. You simply say:

“I think this is a problem. I think we should stop dancing, before we get in trouble or anything.”

“Your problem is my problem,” she says.

“OK. We won’t dance ever again.”

The office girl looks hurt but nods. “Good. Fine. I’m quitting here anyway.”

“You are?” you ask.

“I am,” she says.

“When?”

“I don’t know when. I only know I’m done with this place. I’m moving to Guam. Or Cambodia. I haven’t decided.”

Your face is red for some reason. She stares up and frowns and then says:

“I thought I liked you. I thought you were going to be decent. I’ve wasted time thinking about how nice you were, but you’re not nice, are you?”

You shake your head and back away slowly.

When you come into work the next evening, a small man with a black mustache is at the office girl’s desk. You leave two notes for the HR person, trying to get Odille’s phone number, but your company has a strict policy, and like that, the office girl disappears into the unfriendly faces of the fading metropolis. What has gone wrong? What sort of mess is this life anyways? you think.

On the bus, riding back to your apartment in the morning, you see a girl with a brown scarf and think how it might be her but you know it is not and you realize the world is peopled with ghosts. Here you have had this whole idea of what was going to happen and it has not happened and why did it not happen? You look and look and still you do not know. At work the next evening, you beg Amanda from accounting for the office girl’s phone number. She shakes her head and says, “No,” but emails it to you later that night anyway.

You spend all evening staring at the number, the number which you have written on the back of your hand. You are imagining doing everything right this time and just confessing how much you really like her. You really, really do. You are thinking about one moment in particular, the best thing that’s happened to you all year. It goes exactly like this:

The office girl, Odille, laying beside you in her bed, with her white face flushed red, looked at you and said:

“I am going to bite you now.”

“What?”

“I am going to bite you.”

“Why?” you asked.

“Why not?”

“Because it will hurt,” you said.

The office girl, Odille, leaned beside you and placed her mouth near your ear. The two of you must have sat like that for a hundred years, neither one of you moving, until finally, you asked “What are you doing now?”

“Your one ear is smaller than the other, do you know that?”

“Yes,” you said.

“Shhhhhhh. We are the only two people left in the world.”

“What?” you asked.

You looked at her and thought you would be happy to lie like this forever maybe. Then she said it again:

“We are the only two people left.”