A thirty-six-year-old unmarried woman joins an online dating site, and so does a forty-year-old man who is married to a woman he may or may not still love. The woman’s profile declares things like “loves reading, learning to cook exotic foods, and swimming in natural bodies of water.” The man’s profile states that he “enjoys restoring old furniture, late-night movies, and reading biographies of historical figures.” In actuality, the man hasn’t restored any furniture since before his children were born, and the biographies of historical figures are actually biographies of sports icons. Likewise with the woman: she hasn’t swam in a lake or ocean in over seven years, since her sister’s bachelorette party, and the reading and cooking are more things she would like to do than things she actually does. They both post pictures of themselves from ten years ago, with better haircuts or just generally better or more hair. They only use first names because you can’t be too careful on the internet. After two months of exchanging emails and chatting online, they decide to meet.

He lives in a city three hours away from her, but registered on the dating site in her city to avoid awkward run-ins with people who might know his wife, which he explains away to the woman by saying he is looking to move to her city soon, so what’s the point in dating in his? Now he is coming to visit her, coming on a train because he’s actually never been on a train, and she loves trains and insisted that he has to ride one once in his life, has to pay attention to the landscape sliding by the windows, which you never pay attention to driving a car, has to walk up and down the train cars while it’s moving until he masters it, can stay steady on moving ground, gets his train legs. This was part of one of their many conversations about the small joys in life and the things they have and have not done and still want to do, which seem to them to be more in-tune and romantic than any conversations they’ve ever had in person with anyone. They are amazed at how well they understand each other. The woman wonders if it is possible to meet your soul mate on the internet at age thirty-six, and the man wonders if he married the wrong woman fifteen years ago.

The woman doesn’t know which train he’s on. All she knows is that she’s meeting him at an Italian restaurant at eight o’clock.

There is a train wreck. It’s not the train the man is on, because he never gets on a train at all. He goes to the train station and stands in line and can’t go through with it. His bag feels too heavy, packed with two changes of clothes and a roll of condoms. The cash he withdrew as to not leave a paper trail is a treacherous bulge in his wallet, a palpable wad of his deceit. He thinks about his wife at home making lunches for his kids, thinks about how there was a time when he drove five hours every other weekend to see her when he went back to business school so he could support a family, support her. He can still feel the brusque kiss he gave her this morning as she got out of the shower, thinks he can smell her shampoo on his cheek. The emails were one thing, but the idea of sitting across from this woman and smiling at her and perhaps holding her hand across the table (which is what he imagined he would do) makes him feel hypertensive, and when he looks at his hands he can see his veins bulging green and wormy under his skin. He feels very old and wonders about his blood pressure. He steps out of line and drives home, tells his wife the business meeting out of town was canceled at the last minute. His business contact had a sudden heart attack, but it looks like he’ll be fine.

But the woman goes to the restaurant not knowing about the man’s defection or about the train wreck. She puts on a new dress in a dark green that complements her skin and makes her chestnut hair look lustrous, wears lipstick for the first time in months, and sits at a table facing the door. She brings the photograph of him from ten years ago that she printed out at home, in which he is too orange—something is wrong with her printer—and she holds it up every time a man walks in. When it becomes eight o’clock and he’s not there yet, she tells herself that he’s running late. She had given him her phone number in an email, but he had forgotten (purposefully?) to give her his, so she can’t call him, but maybe he’ll call her. She places her phone face up on the table. She goes ahead and orders a glass of white wine.

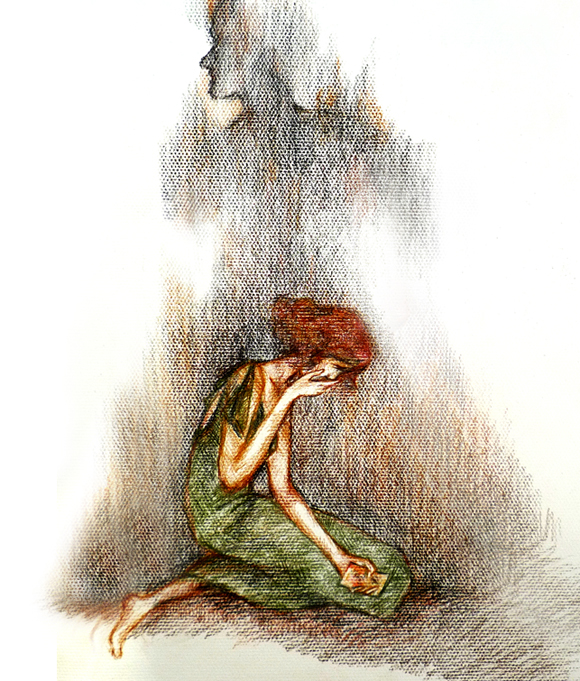

When ten minutes have passed, and then fifteen, she becomes self-conscious that the wait staff is watching her, pitying her. She drinks several more glasses of white wine, so cold the glass wets her fingers, to calm her nerves, but it doesn’t work. The wine lands cold in her stomach and feels as if it doesn’t stop there but keeps on falling to the floor, through the floor, through the foundation of the building and farther, as if there’s a large hole in her that plunges straight down into the earth, like she’s a sinkhole waiting to open up. The photo in her hand shakes with as if with mocking laughter. She wants to crawl through the hole in herself and sleep somewhere in the dark soil without an internet connection. And then she starts to hate him. Who is he to stand her up? He’s forty, for Christ sake, there must be something wrong with him that he’s still single, especially looking as cursedly handsome as he does. She wonders what his flaw is and focuses on it as she finishes her last glass of wine after sitting for a little over an hour at the table: maybe chronic bad breath, an annoying laugh, self-obsession, a tendency to interrupt when others are speaking, a small penis, a foot fungus. She pays her own bill, which she had been expecting him to pay. She tips poorly.

When she gets home and turns the TV to the news, there it is on the screen: the smoke, the burning, the twisted metal, the ruined dotted line of the train as seen from a news helicopter above. It’s on every news channel: two trains collided, the passenger train and a freight train carrying chemicals, at least twenty presumed dead and the count rising. She immediately thinks that it was his train. It was going from his city to hers. She thinks she made him ride a train and he did and now he’s dead and she’s responsible. She thinks of the horrible things she thought about him in the restaurant and pulls his photo out of her purse, and as her hands shake, his image quivers like a last breath, like an eyelid closing, like his spirit dissolving into the smoke over the burning train. She imagines his body mangled and burned, that body she was planning on running her hands over that night, that body with moles and chest hair she had been looking forward to learning and loving fondly in its imperfections. That sweet man, riding a train headed for her. They have not yet released the names of the deceased so they can contact their families first, notify their loved ones, and the woman wonders if she would count as a loved one, maybe not yet, but eventually.

She turns off the news and reads all of his emails, all of his chats. She goes to his profile on the dating site, and everything is just the same as it always was, and she doesn’t know what she thought would be different, of course it would not be instantly updated with his death, but it seems especially cruel that it’s still there, listing his interests, his hobbies, his birth date without the death date, his picture still there, eyes crinkling with his smile, as if he’s right on the other end of the internet, waiting to meet someone special, and all she has to do is click “send.” She sends him an email. She nurtures the small blossom of hope in her heart that maybe it was not his train. Maybe his train was coming after that one and so it was delayed and that’s why he never showed up at the restaurant. In the email, she asks, “Were you on that train? Please tell me you weren’t. I’m so sorry I told you to take a train.”

He doesn’t see her email. He goes home and dreads how he will have to break it off with the woman. He feels some responsibility to her even though they’ve never met. He feels he knows her very well, and she knows him, understands him like his wife doesn’t anymore, except she doesn’t know he has a wife, and perhaps she wouldn’t understand as much if she knew about that. When he goes home, he takes off the new boxer briefs he bought for the woman and makes desperate love to his wife while the kids are in school, which they haven’t done like this in months, not during the daytime anyway, and she is pleasantly surprised and blushes at him as he tugs off her cardigan, and he feels his love for her expand like a collapsed lung un-collapsing, finally letting him breathe. He looks at the back of her head while she dozes afterward and thinks of how stupid he almost was. He remembers how things were when they first met, in the first years and months. He remembers how he felt the same way about her as he feels about this woman on the other end of the train. If they had a relationship, it would have gone the same way, he tells himself. They would run out of conversations, their excitement would degrade into complacency, their feeling of possibility would fold into itself until it was a grocery list of paper towels and Metamucil and children’s chewable vitamins wadded in a pocket. He tries to craft tomorrow’s email to the woman in his head. What will he say? Can he tell her he has a wife? That would probably do it.

He sees the woman’s email the next morning, in the secret email account he set up just for the dating site. He hadn’t even heard about the train crash yet, having spent last night with his family with the TV off. But then he realizes his opportunity; he guiltily, shamefully realizes his opportunity, his out. Let her think I am dead.

And she does. By the time the names are released, she has already decided he is dead, but she reads the list anyway and finds three dead men with his first name, and she puts their last names in her mouth, feels them with her tongue, trying to determine which one was his, thinking she should be able to tell. She drives to his city, too afraid to take the train and the track still being cleared of wreckage anyway, and goes to the memorial outside the train station and leaves her orange computer printout of his picture propped against a candle.

She mourns him. She mourns him as if he were her true love, becomes convinced he would have been her true love, mourns the premature loss of the life they would have had together, the beautiful life they would have had. She makes up conversations with him in her head, how everything would have been perfect in the restaurant, how they would have gotten drunk on wine and taken a taxi back to her place and discovered their true selves in each others’ bodies. She already misses the late-night movies they never watched, the antique furniture they never restored, the books they never discussed. She stays away from dating websites for awhile, still too fearful of all the possibility that could be abruptly found and taken away.

Years later, when she has a new boyfriend she met on the internet and it’s going well, but not perfectly, she still sometimes returns to the emails and chats she saved on her computer and re-reads them and thinks of the life they could have had, their love still pure and unconsummated, preserved in a binary of x’s and o’s.

Like the story? Check out the print edition.

Read more about Claire here.

Read more about Robin here.

I love this! You really captured some of the highs & lows of human emotion beautifully – particularly from the woman’s perspective – the wholeness and pureness of what could have been. Bravo 🙂

Beautiful work, Claire.

Wonderful writing.I could really felt the emotions in the woman when I read it- a sadness with the loneliness of human-being.

Love the story. Its predictable, simple and I think that’s where the mastery in this piece is: keeping the story simple, predictable yet engaging with a dash of humor.

fantastic.

oh please.. this story plot has been done to death- come on annalemma, dont you want to be unique? or is it a friend?

@rachel: I’ve never met Claire in person. What makes this piece interesting to me is the characters and the narrator’s voice. The plot structure may not be unique, but show me a plot structure that’s got an interesting level of drama and conflict that hasn’t been told a thousand times over. Sometimes you use the same tools over and over again cause they work.

This is a wonderful story: well-written, realistic characters, charming and distressing at the same time.

me think thou all protest’eth too much

Brilliant. Easy going, yet very impressive indeed.

Super story, I loved the feelings expressed.

Well done! Excellent.

Really nice. Compelling.

Beautiful! There is something very Haruki Murakamiesque about it.