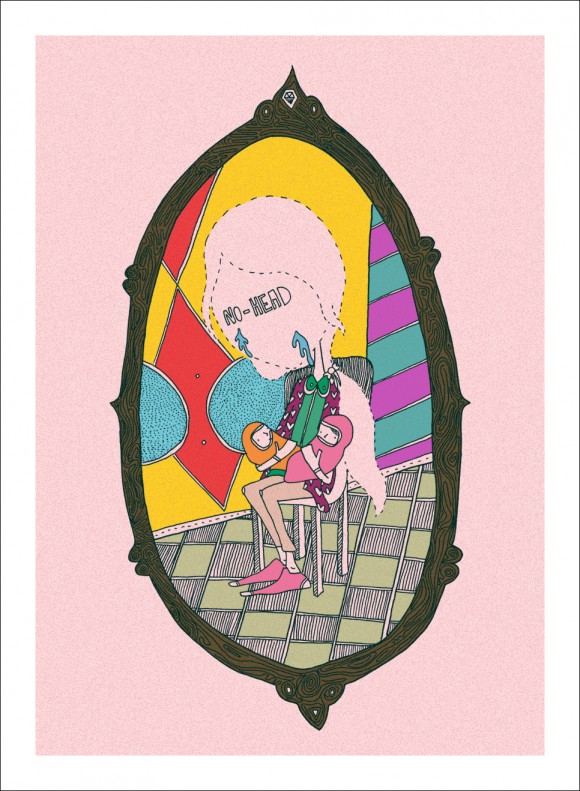

The first reported case came out of New York. No-Head, they called her, and my husband and I sat mesmerized in front of the evening news, staring at the space where her neck would normally have met her head as she spoke through her invisible mouth, cried tears out of her invisible eyes, and blew snot from her invisible nose. A mother of colicky twins, her head simply disappeared one night as she was rocking them to sleep.

The next week, seven more heads vanished. The week following, forty-five. Scientists believed it was a side effect of depression, and subjected the headless to heavy doses of anti-depressants, skin-strengthening serums, and hours and hours of sitting in the sun, after which they complained of sunburns that no one could see. Nothing worked. Meanwhile, heads continued to disappear – while people were skydiving, getting married, watching Hallmark commercials, hitting the jackpot at the casino. Scientists agreed that the condition was not solely related to depression, but instead to extreme emotion of any kind. By the end of the first year, nearly one in ten people were headless.

“They look funny when they eat,” I said to my husband while we were dining out one night. Mark didn’t answer, only followed my gaze to the headless couple at the table next to us. A set of forks disappeared and reappeared without food. Noodles dangled before being sucked up into the void. No evidence of chewing, swallowing.

I took a bite of buttered bread and asked him about work. He said he’d had a bad day and we changed the subject. He asked me if I’d stopped by my mom’s house to help with the garage sale she was putting on that weekend. I told him that we’d barely escaped a fight, and he nodded, leaving the conversation at that. That was how we’d learned to live – with shrugs and changed subjects, with cautious questions and quick, careful answers. We’d put off having a baby until the whole headless phenomenon took care of itself. Really, we’d put off everything. We never saw movies anymore, never watched sports. Just to be safe, I gave up chocolate. Mark gave up whiskey. There were purists that believed that if you weren’t headless, you weren’t living. They waved signs in the middle of Times Square touting their emotional supremacy. Those of us with heads rolled our eyes. Just because we could.

Once a month, Mark and I went to meetings where people with still-visible faces found support to speak of the things they’d been holding back. At these meetings, friends came clean about stabbing each other in the back, siblings admitted to stealing each other’s clothes, spouses informed each other of big promotions or lumps in the breast. It was here, almost two years after the first headless woman appeared in the news, that I finally told Mark I couldn’t take it anymore, that his touch had begun to make me squirm. In response, he calmly told me that my voice grated on his ears like a knife scraping along a ceramic plate. In front of twenty-five onlookers, we decided to divorce with only slightly feigned casualness before returning to his car to engage in a perfunctory session of goodbye sex.

Only three weeks later, I ran into Mark at our favorite Chinese restaurant. He was holding hands with a headless woman across the table, staring lovingly into her void. “I didn’t see any point in telling you before,” he said when I asked how long this had been going on. I could feel the headless bitch staring at me. “Sheila and I are engaged.”

I walked away. The next day, I learned that I was pregnant. I couldn’t bring myself to tell Mark, and so I didn’t.

As my belly grew, I kept myself busy, trying to stifle the anger I felt toward my ex, trying to ignore the little person inside me that kicked and prodded, raising the skin on my stomach. I took up yoga, practicing for up to three hours per day. Whenever I was out in public, I focused all of my attention on the headless people, no longer concerned with whether or not they might be staring back. This invisibility, this lack of self what I was working to avoid. It was worth it, I told myself over and over again. It was worth it.

When my water broke, I fought hard to maintain my best yogi trance, feeling the pull of the contractions but not working against them, letting the baby go down, down, down. I never even said ouch.

“Are you sure you don’t want to hold her?” a nurse asked mere seconds after I felt the release. I clamped my eyes shut and shook my head, trying to close myself off from the room, but all I could hear was the sound of my baby crying. A while later, the nurse approached, holding my bundled girl in her arms. Adrenaline shot up through my veins and I shook my head again. “No,” I said, “not yet.” She stepped forward anyway and placed her in my arms. I only glanced down, but that was all I needed. My child, only fifteen minutes old, was already wearing her emotions on her face. A pink cotton blanket encircled the nothingness of her head, keeping her warm, holding her tight. Her neck was beautiful. The most beautiful neck I’d ever seen. I could feel my features tingle as they disappeared – my nose first, followed by my mouth, then my eyes, my cheeks. Within moments, my head was gone.

If only you could see the smile on my face.

Like the story? Check out our print issue.

Read more about T.L. here.

Read more about Herbert here.

Well written. But sometimes it feels hollowm as if it’s written just for the sake of it. I wanted to like it, even did, most of the time; but all in all it was a disappointing read, the last third of it being painfully predictable.

terrific story. i disagree with the comment above, immensely. i think it’s a great commentary on the impossibility of avoiding extreme emotions throughout life, no matter how hard we try to contain them or wish them away. some things in life are, well, just too powerful to avoid — and, besides, isn’t that what makes it so beautiful? i love this so much, i blogged about it.

i read this last week and was too embarrassed to comment, but this story is actually amazing. i would (and will) recommend to others. thanks!

unbelievable that in such a short space the writer has concocted such a powerful message about the human condition. this is a real eye-opener of a piece and most certainly meant to be read over and over again. it’s quite timeless.