Like so many cities once or currently the seat of empire, Istanbul assaults the senses. There is simply too much coastline, too many hills, too many mosques, shops, hotels, apartments, restaurants and cafes ill-fit for the space they fill they are like the striations of a canyon wall: here the sediment of Byzantium, over it the Ottomans’ mosques and palaces, the few remaining wooden yalis, on top of it all Turkey’s attempts to modernize – glass and steel towers, concrete slabs of housing.

In the old city and in the shopping districts of Beyoglu, the scents of roasted chestnuts and corncobs waft everywhere. In the Grand Bazaar and Spice Market curry predominates. In the narrow, crowded streets and alleys that never seem to come out where they should, in the crush of those walking seemingly heedless of each other and certainly heedless of the vehicles whose drivers are brave or reckless enough to try negotiating the city’s maze, the aroma is stronger still.

Punctuating its sights and smells are the calls of the city’s ubiquitous salesmen, who lurk in store entrances waiting to accost an unsuspecting mark, usually a tourist, beckoning with a common refrain, “Yes, please.” A few decibels above their pleas, ferries, cruise ships, sightseeing boats and tankers announce their Bosphorus passage. Over it all hovers, five times daily, the muezzins’ calls to prayer.

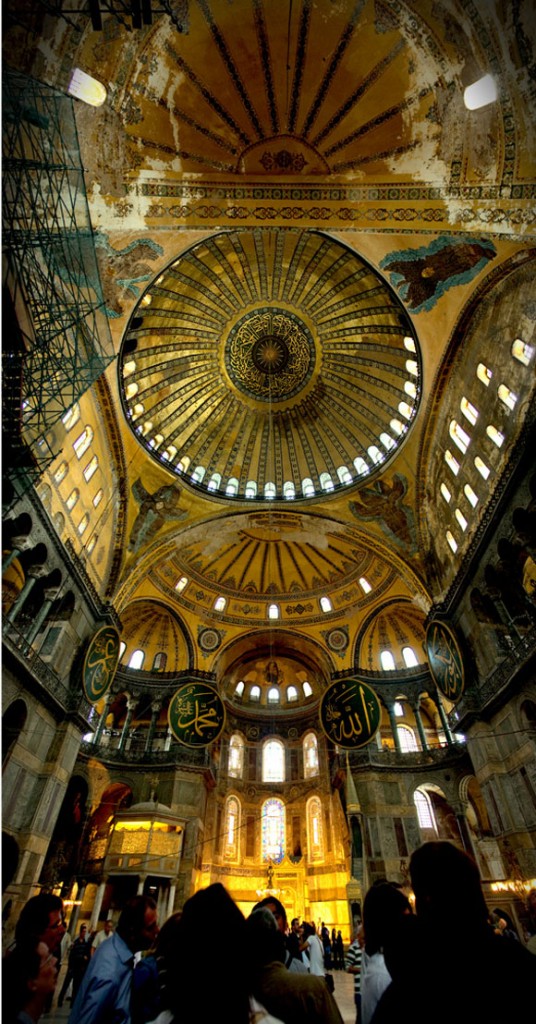

Despite its history, culture and religion, Istanbul is first and foremost a market city and what it markets is, unsurprisingly, its history, culture and religion. As a result, the city is a tense conjunction of tradition and modernity, the line between appreciation and exploitation indistinct. My wife and I entered the Blue Mosque one afternoon shortly after prayer and, though the area for worship is set off, walking around snapping pictures while people prayed seemed at best intrusive, at worst sacrilegious. To compound the matter, women pray in a separate part of the mosque, one decidedly less isolated from tourists. Wedged where they were, in a corner between two entrances, the women weren’t congregants so much as mannequins in a religious museum’s diorama. Of course, the mosque benefits. Though entrance is free, donations are strongly suggested.

Conversely, the whirling dervishes are marketed specifically for the purpose of charging admission. Members of the Mevlevi Order, for more than 800 years dervishes have whirled as a means of abandoning their earthly egos and seeking perfection with Allah. I, along with 200 other tourists, paid 40 lira to cram onto a hard, metal chair in a bare, cavernous room and watch what should have been an intense individual spiritual experience.

Individual spirituality is a fairly recent phenomenon in the West, a product, essentially, of the Reformation. Meditating, or in this case whirling, to achieve a state of grace is more generally the practice of Eastern religion. However, as a border city, Istanbul has been a place where empires and their adhering religions have collided for two millennia and, as with everything else in the city, relics of different religions can be found intermingled. In the Chamber of the Sacred Relics at Topkapi Palace, these include a cloak, sword, tooth, hair and letters of the prophet Mohammed, Joseph’s turban (Genesis’ Joseph, not Jesus’ father), Moses’ staff, and the once entrance carpet to the Kabba.

As my wife and I made our way through the chamber, what I thought was a recording of the Koran played. Only at the exit did we pass a young adherent chanting into the public address system and realize it wasn’t a recording after all. Standing before this turbaned young man, intensely self-conscious in my tattered Red Sox hat, watching and listening to him read the Koran as an English translation of it rolled on a video screen next to him, I wondered: Does the West’s intense materialism leave our society, at its core, hollow? If we do teeter on the precipice of a titanic struggle between civilizations, does this hollowness not place us at a disadvantage? As tourists, do we exploit Islam by commodifying it as an attraction? Don’t the Turkish authorities also exploit it by advertising the religion for the same purpose? If tourism is, then, exploitative, even imperial by implication, by what other means can cultural understanding be achieved, or, even, can it? And, if it can’t, how are we to avoid the pending struggle between our societies?

Likewise, there are the economic questions. If tourists didn’t flock to Istanbul, most of whose hotels, restaurants, cafes and shops rely on foreigners, how would their proprietors make money? Does that not then make our visit propitious? Without the capital tourists pump into it, would there be enough available locally for Istanbul’s economy to expand? Is not the foreign investment tourists provide in ways preferable to the larger investment of foreign firms and banks, as the money that exchanges hands between tourists and local proprietors is more likely to remain in local circulation?

Absolutely everything in Istanbul is for sale and organized for the purpose of selling. In the city’s older districts, which lack department stores, shops restrict themselves to a single product and, by design or accident, shops that sell the same items tend to be located in the same neighborhoods, on the same blocks even. For instance, all the lighting stores in the city huddle together in Galata, on the western slope of the hill below the tower, all the music stores on the Iskatil Cadessi, which stretches north-northwest from the tower into the heart of Beyoglu and, with a cut back to the east, finally to Taksim Square. But, if you are a tourist, you are not looking to buy track lighting on your trip to Istanbul. It is, of course, a Turkish carpet you want.

There is an inexorable undertow to the experience of buying a Turkish carpet. It can be difficult to resist the salesman’s pull. In the finer shops he seats you, serves you tea and presents his wares one rug at a time, unfurling them with a flourish, giving you the history of their design, the regions in Turkey from which they hail and the materials used to mix the colors in which their thread is dyed. Once you’ve seen the available inventory, the salesman takes you back through the rugs and divides them into two piles, those you like and those you don’t. The discarded pile is whisked off and the sorting exercise is repeated, as many times as is necessary to whittle the pile you like to two or three carpets. It is then the haggling and, I would argue, the fun begin.

For someone from a Western culture in which two centuries of an increasingly complex division of labor and emphasis on upward mobility have stigmatized salesmanship, with the result that most of us conceive of prices as fixed, haggling can be uncomfortable. Do it enough and it becomes nothing less than addictive. Toward the end of our week in the city, though we had already bought two carpets and had made a pact to buy no more, my wife and I passed a shop with a woman sitting in the window weaving. We stopped to watch her. Of course, she was a plant, there to snare tourists. Sure enough, spotting his mark, a salesman stepped out, invited us into the store and began explaining the double-knot technique employed in Turkish carpets, assuring us the whole time there was no obligation to buy, despite which, the next thing we knew we’d been seated, served tea, had examined enough rugs to carpet a football stadium, and whittled the pile we liked to one – a wool on wool design created with only the natural colors of white, brown and black sheep. We were tempted, but the salesman quoted us 1800 lira and, at that point, recovering our senses, we prepared to leave.

An older and considerably more suave gentleman stepped in to salvage the deal. Clearly the closer, he asked the top price I’d consider. Hoping to end the negotiation before it began by quoting a price so ridiculously low he’d never consider it, I said 300 lira. To my surprise, he dropped to 500 and like a large-mouthed bass I took the bait and moved to 400. He countered at 450, but this time I held. He came down another 25, but, not really caring about the rug, haggling only because I enjoyed denying something to another person, I again refused to move.

Finally, he asked point blank if I’d move off 400, even a single lira. Again I said no. At this point I honestly believed that, even if he gave into my demand, I wasn’t actually going to buy the rug, but then he shrugged his shoulders, stuck out his hand, smiled and said, “Deal,” and I whipped out my credit card like a gunslinger in a duel at twenty paces. All the while my wife looked on horrified.

In my defense, the best salesmen really are that good. You will be signing the credit card slip before you know they’re selling you anything. And there is clearly a sales hierarchy, younger salesmen serving apprenticeships with their more experienced brethren. Spend enough time haggling and you gain both an appreciation for the smoothest salesmen and a critical eye for those who all too often telegraph their intentions with awkward overtures.

The best salesmen seem less interested in the final sale than they do their own performance. Nevertheless, that everything is for sale and that the salesmen are generally so forward can, in the end, be wearying. You soon realize the only way to negotiate the city’s streets and alleys, where salesmen accost you at practically every step, is to ignore them. Despite the incessant pitches, though, the careful tourist is in an almost unbeatable bargaining position. They have the leisure to browse the city and negotiate the lowest possible prices for items they don’t really need. And, together with the salesmen, it has to be asked whether they are, in fact, taking complete advantage of the women who weave the carpets.

There is clearly a gender difference in Istanbul. During our time there, we encountered only four women employed in public positions: a guard at Topkapi Palace, a bank clerk, a clerk in a ticket booth for one of the ferries that criss-cross the Bosphorus, and a waitress in a hotel bar where we stopped one afternoon for a drink. Every other salesman, waiter, security guard, cab driver or hotel clerk was a man. In this paternal hierarchy, women weave and men sell. We were told that, as education and employment opportunities for Turkish women improve, the art of weaving is disappearing, but until then it remains a matter of simple math. We purchased a carpet for 400 lira that, by hand, must have taken months to sew. Subtracting the wool’s cost and the salesman’s commission, the woman or women who wove the carpet couldn’t have earned more than pennies per hour for what is both painstaking work and a magnificent artistic achievement.

None of this need be considered by the average tourist, however. Being a large, cosmopolitan city, Istanbul doesn’t require you confront difficult questions of culture, religion and economy any more than spending a few nights drinking in the French Quarter requires you to confront New Orleans’ otherwise rampant poverty. Get outside Istanbul, however, and it is another matter entirely. Nowhere was the line between capitalism and exploitation more muddled than in a little coffee shop at Arundali Kavaggi, up the Bosphorus almost to the Black Sea. The shop was quite literally a family’s home, occupying what would normally have been the front parlor. The bathroom available to patrons was the same one the family used, the shop owner an overly solicitous gentleman, and the young girl who ran the kitchen the owner’s daughter.

Capitalism has raised millions, if not billions of people around the world out of poverty. Still, the casualties it leaves in its wake can evoke an uncomfortable form of pity, one likely neither sought nor welcome and, even if it were, would still be impossible to assuage. To dine for prices we considered a pittance and then relieve ourselves in this family’s home was to violate. However, not to would have been to abandon.

Read more about Liam here.

Read more about Chase here.

The author’s detailed descriptions and below-the-surface thinking combined to create a rich layered travel article. As a U.S. American living in Latin America for the last 14 years, my conscience squirms uncomfortably as I ask some of the same questions but few answers (and definately nothing novel).

I feel the same way about this one. Lots of questions, lots of possible answers, nothing definitive, just have to see how it plays out. Just like life.