I’m trying very hard but oh my god she’s moving too fast. I told her I can’t dance. I said really, I can’t dance. But she made me go anyway. So here I am looking like a fool. I can’t even do the basic step right, the one-two, one-two. So how am I supposed to spin her or catch her or dip her or show her off to every man in the room, each half as drunk and half as old as me? She’s mad at me because of it. I can see it in her face. There are wrinkles where there shouldn’t be wrinkles, on her cheeks and at the corners of her mouth (she has aged better than me), and this means that she’s mad at me.

When we get home she’s going to say, You should’ve told me you couldn’t dance. I’ll say, I did tell you I couldn’t dance. Then she’ll take to sobbing again and I’ll have to ask her to go do the crying business in the closet. The problem with this is that she will actually go to the closet and sit down inside of it and close the door. She’ll get really quiet and then after I’ve forgotten that she’s in there she’ll come out and ask me why I don’t love her anymore. Then I’ll have to spend the next hour explaining why I don’t love her anymore.

I’ll begin by saying: Dear Charlie. Her name is Charlie. I like that name on a girl. Especially when that girl is pretty. And this Charlie is knockout pretty. She’s my sunshine girl. I’ll ease into it with that. I’ll say, Dear Charlie. Dear sunshine girl. I used to love you. You know that. You’d wake in the morning and you’d dress slow in the bedroom instead of the walk-in closet so I could watch. You’d parade yourself around the room so I had time to see you. I always liked how you did that.

Of course this is as far as I would get. She’d start yelling at me. She’d shake. She’d shake like she’d been in the rain and was soaked through. She’d shake as if she were covered in rainwater and standing in the frozen goods aisle at the store. Only it wouldn’t be the cold this time. It would be something else. It would be her desire to make my lip bleed.

I’d try to hug her. I’d say, Dear sunshine girl. Only now-a-days you put my day to gray. She’d yell at me here because I said something stupid, plus what I’d said rhymed, and this would make her want to yell louder. She’d say, God you’re such a bad poet and then I’d say, I’m not even a poet I work in computers.

She’d go back to the closet and take to quiet sobbing, just loud enough so I could hear her even if I had the TV on, which I would. I’d be watching baseball even though I hate baseball. Or I might be watching tennis, which I like only marginally better.

Eventually she would come to me. I’d be sitting on the couch. She’d come and her mascara would be all over her sleeves and I would admire how beautiful she is. She would say, I don’t love you either, so there, but it would be a lie and so it wouldn’t really hurt my feelings. I would ask her if she wanted me to make lasagna, if that would make her feel better. She would say no but I would make it anyway because I know it’s her favorite food. She would eat more than she should. I always liked that about her. She was okay with being imperfect.

The meal would end and I would continue with the previous theme by saying, Dear Charlie. Dear sunshine girl. I don’t love you anymore. I used to, you know that. There were so many things that you said and I was in love with you because of them. None of them were terribly important but they were all terribly beautiful. You’d say things like, I wonder where the fish go in winter, when the pond freezes. You’d say things like, I wonder what it might be like to dine at the bottom of the ocean. You loved the water. You always loved the water.

Dear Charlie. Dear sunshine girl. I remember loving the way your hair felt after the ocean, maybe like construction paper. We’d go to the beach. It was never quiet because of the waves. And you never liked the sand. You preferred a rock beach and the way the sea was more vicious and cold in these places. But still you were never afraid to enter and swim farther out than you should. I never joined you. I told you it was because I didn’t know how to swim. But really I was afraid. I’d wait on the beach and I would watch you, wondering when you’d sink beneath the surface. Sometimes you would and my heart would stop as I waited for you to rise, wondering if perhaps this time was the time that you’d stay down forever.

I would get to this part about the ocean and she’d say, Let’s go to the coast and swim. She’d say, This time you can swim too and I’ll take care to never let you sink. But I’d say, I have work in the morning. This would be a lie because the next day would probably be a Saturday.

She’d stare at me for a moment, waiting for something, I don’t know what. I’d say, Dear Charlie. Dear sunshine girl. I used to love you but I don’t anymore. Let me give you a list of five thousands reasons why. One, time has been kind to you, but not to me; your face is beautiful so when we are eating in a restaurant or when I am trying to dance I can’t help but hate the people who are watching us, every one of them wondering why I have a girl like you in my arms. Two. Three. Four. Five. Eventually I would get to five thousand, though by this time she probably would have fallen asleep.

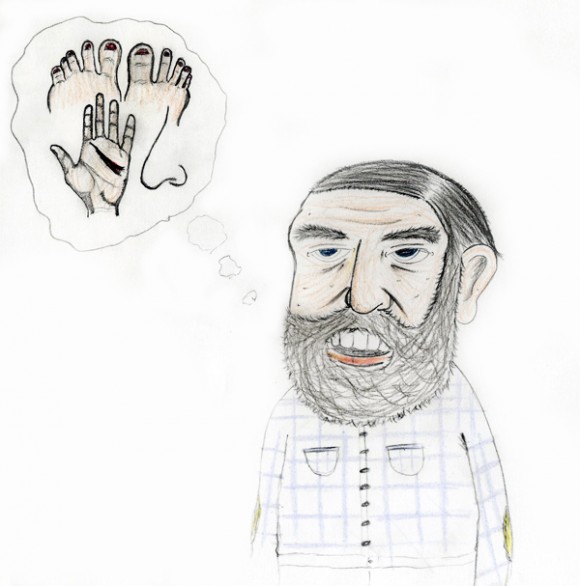

I would carry her to the bed. I would undress her. She prefers to wear an extremely large shirt to bed, one that falls past her knees. So I would put this on her and I would put her in the bed. I would sit there and watch her. I would admire her features. She was and always had been beautiful in all the ways a woman should be. But there were little imperfections and I always liked these particularly: the small dip on the ridge of her nose, the scar on her palm (have you ever met a person with a scar on their palm?), the way her left pinky toe was visibly fatter than her right one. I would sit there and I would admire these things, but would inevitably arrive at the conclusion that these are not enough and so I would rise and I would leave. I wouldn’t take anything except my clothes. This is what I would do if I were the person I like to think I am. But really, I’m not that person.

I’m trying very hard but oh my god she’s moving too fast. I told her I can’t dance. I said really, I can’t dance. But she made me go anyway. So here I am looking like a fool. I can’t even do the basic step right, the one—two, one—two, whatever it is. So how am I supposed to spin her or catch her or dip her or show her off to the world? She’s mad at me because of it. I can see it in her face. There are wrinkles where there shouldn’t be wrinkles, on her cheeks and at the corners of her mouth, and her eyes are pale and static. This means that she’s mad at me.

When we get home she’s going to say, You should’ve told me you couldn’t dance and then all I will be able to say is, I’m sorry, I must have forgotten that I didn’t know how.

Read more about Ian Bassingthwaighte here.

Read more about Juston Tucker here.

well written and interesting. Thoroughly enjoyed it

stunning, beautiful, killer

Thoroughly enjoyed it, though I could not much make sense of the transition to ‘She’ somewhere in between.