Sirens. I pull over on the shoulder of the interstate and retrieve my registration from the glove box. I watch in my rear view mirror as the officer writes something. He gets out of his vehicle and approaches my car.

“Morning, sir,” the officer says. “Any idea how fast you were going?”

“None.” It is early. I am terse. I do not have time for limits.

“Well, you were doing seventy-five when I caught up to you, and you had already been on the brakes at that point. Mind if I see your license and registration?”

I hand him the documents and reposition my hands at ten and two. The officer retreats back to his car, presumably to check and see if there’s a warrant out for my arrest.

A few minutes later he returns, a yellow piece of carbon copy paper clearly in his hands.

“Where you headed this morning in such a hurry?” he asks. I don’t look at him.

“Canada,” I say.

“What’re you doing there?”

“I’m going to save my brother.”

“Save?” This is clearly a conversation the academy didn’t prep him for.

“Yes.” I match his gaze with a grim look.

“Look, I’ve got to write you a ticket. I’m not gonna hit you for negligent or anything like that, just slow down.” He hands me the citation, grey graphite etched on top of a piece of goldenrod bureaucracy.

“Thanks,” I say, taking the ticket from him. “Can I go now?”

“Yup. Have a nice day.” The cop walks back to his car.

That is the last time I tell anyone the truth about my brother.

My brother and I are twins, but we’ve never looked alike. My earliest memory of my brother is of us riding on tricycles at my grandmother’s house in Arizona. As I took slow, labored circles around the driveway, Ethan engaged in a three-wheeled kamikaze mission, pointing his front wheel directly at me and pedaling as fast as he could until he collided with me, sending me tumbling over onto the red concrete that plagues so many Arizona driveways. Each time he struck me I looked at him, shocked. Eventually, I got back onto my tricycle and continued my circles. Ethan inevitably attacked again, sending me flying to the concrete. Never did I hit him back. Never did I tell him to stop.

When I arrive Canada, at the fraternity house where my brother lives, he is out in front to greet me. He is wearing sweats and a t-shirt and, despite it being 4 p.m., he has just woken up. My parents have asked me to come up to help my brother settle in for his second semester, hoping that my guidance will help him avoid a repeat of his first semester antics, a disastrous ballet of poor study habits, insecurity, and mild drug use.

“Hey buddy!” he says, greeting me like we’re best friends. “How was the drive?”

“Fine.” I won’t tell him about the ticket.

We walk into his room, a small single on the third floor. It is an abstract collision of posters, clothes, and books. The room reeks of marijuana and cheap vodka. A glance in the trashcan reveals condom rappers, empty cans, and a copy of Hermann Hesse’s Siddartha. I pick it up.

“Why’d you throw this away?”

“I fucking hated that book,” he says. “Not worth reading, not worth keeping.” I set it back in the trash can.

“I’ll take your garbage out for you,” I say. This is me guiding you. This is me being the big brother that an hour and a half made me. This is me saving you.

When I return to the room, Ethan is concentrated on rolling a joint. “What are you doing? It’s 4:30, don’t you have stuff you have to do?”

“We’ve gotta celebrate man, I mean, you’re fucking here, like here, in Canada.”

I don’t respond. He hands me the joint and I light it, not out of desire to feel unlike myself, but simply because declining will alienate him, will set him off, will create friction. I never liked the friction.

When we were in fourth grade, my brother didn’t do his homework for six months. It took the teachers six months to catch him, probably because they were too busy to care and Ethan was too clever to slip up. Every day, he got up from his desk and, accompanied by our teacher, marched dutifully out of the classroom and down the hall to the office, where he pretended to call home. Instead of dialing our phone number, he dialed seven random numbers, often connecting him to an answering machine somewhere, where he explained how he hadn’t done his homework, how he was sorry, how it wouldn’t happen again. He then hung up.

One day, Ethan left a message on the wrong answering machine. The man on the other end called back and told the school the story of some kid who hadn’t done his homework leaving an apologetic voicemail on his machine. The teachers, although oblivious, were not dumb. They knew that it was Ethan.

Our mother drove us home. No one spoke on the ride home. Ethan fidgeted in the back seat next to me.

“Ethan,” my mother said. “Get out of the car and go inside.”

Ethan grabbed his things and skipped inside, gleeful in his guilt.

“Look, you probably already know this, and I just want you to know I’m sorry, but there’s probably going to be a lot of yelling tonight. So you might want to go to your room and turn your music up loud. I’m sorry.”

I looked at my mother, emotionless.

“Ok.” I grabbed my things and walked inside.

That night, from the moment my father came home until the moment I fell asleep, the yelling never stopped. The fuck you’s from my dad were volleyed back by my brother, a ballsy feat for a fourth grader. The next morning I sat at the kitchen table and ate breakfast with my brother.

“Mom,” he clamored. “Can you make me some eggs?”

“Yes, Ethan,” she offered.

Nothing had changed. Everything was normal again.

In the sixth grade, my brother got in trouble for punching a kid after he tripped him in the hall. In eighth, he was suspended for two days for engaging in sexual activity on the campus of his middle school. Two grades later, my brother got caught plagiarizing a paper, the next year he was questioned by police about guitar amplifiers that had gone missing from his high school. The refrain was the same every time I came home after one of my brother’s increasingly precarious deeds: “Honey,” my mom always said. “You might want to go to your room and turn your music up, I think there’s going to be a lot of yelling tonight.”

When I went to my room, the yelling got worse. They had license to let it all out so long as I had stored myself away somewhere. I hid myself in half-empty soft packs of Camel Turkish Silvers, in Seattle coffee shops on Sunday nights, in between the legs of faceless girls, in the solace of reason, in the comfort of being right. I hid from their terror, from their violence. I still hide.

I have been trying to save my brother all afternoon. I have cleaned his room, bought his books, even thrown in a load of laundry. All the while, Ethan sits at his computer, smoking pot and researching Elliot Smith trivia. “Did you know,” he wonders aloud, “that Elliott Smith decided to be a musician after hearing the White Album? That fucking rocks.” All these menial tasks that I do for him I also do for myself. I am self-sufficient. All these things I have done for Ethan. I will not judge him for this. I am simply here to help. I am simply here to save.

“Ethan, I’m hungry. Let’s get dinner.”

“Good call.” he says, enthusiastic about the idea of food. “Afterwards we can go to The Gallery, it’s karaoke night.”

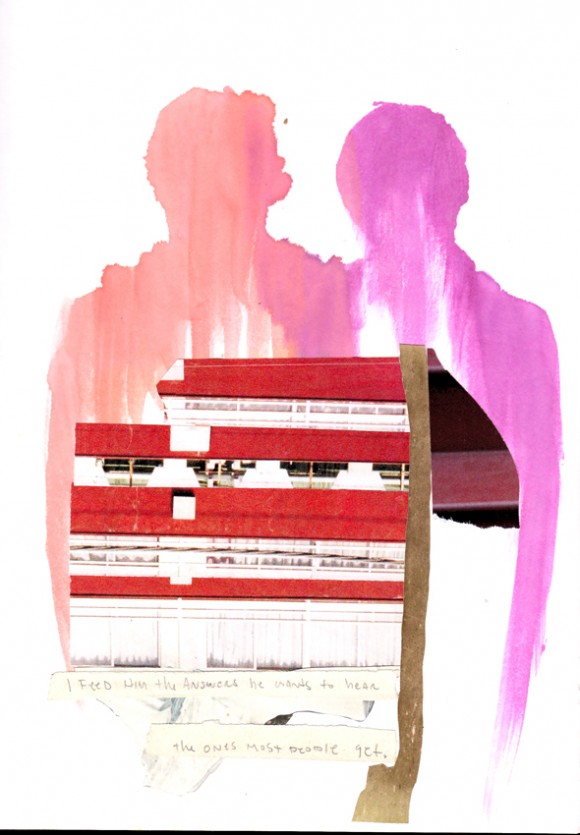

We both drink too much at dinner, perhaps in an attempt to peel the awkwardness away from our interactions. “So, buddy,” he asks, pretending to be interested in my life, “Like, what’s up?” I feed him the answers he wants to hear, the ones most people get. He is no different. I like my friends. I like my classes. I miss our dog. Iowa is cold. I still write sometimes. I drink sometimes. I’ve been in one fight, fucked two girls, aced three tests. The numbers don’t matter, they are just statistics, ways for him to gauge me. He doesn’t know. He’s never known.

“And you, what’s up with you?” I am drunk. I try to hide it but my pronunciation betrays me.

He gives me a summation of his first semester: kicked out of his dorm for punching a kid in the face and breaking his teeth, caught with marijuana, barred from visiting any of the dorms, an F in his economics class, a pregnancy scare, a bike accident that resulted in a concussion, moving into the frat house, allegations of cheating, a scholarship revoked.

“That’s all?”

“And suicide watch.”

After I pay for our dinner, we walk the six blocks to The Gallery, the requisite college bar. Tonight is karaoke night, a drunken homage to the eighties. Ethan and I grab a table, order drinks, sit and bask in the comfort that the bar is too loud to allow for conversation. To the outside world, we simply look like two friends enjoying a drink. No one knows we are brothers, no one knows we are twins. Too many shots later, Ethan is up, singing “Don’t Stop Believing.” Ethan is the drunkest guy at the party, the overzealous karaoke singer. He doesn’t even like Journey.

At two, the bar closes. Ethan and I don our coats and prepare for the walk back to his frat house. We talk about nothing important, recounting the few amusing shared memories that we have amassed together. Their only commonality is that they all happened long ago. Everything funny happened a long time ago.

We make it back to his room. I lie down on a mattress that he has laid on the floor for me. I pretend I am asleep. “Sammy,” my brother asks, his voice getting higher in pitch, mimicking that of a younger child. “Do you love me?”

I pretend I am asleep.

The next morning, I wake up first, as I always have, as I always will. I try to rouse Ethan. I figure I will take him to breakfast and say goodbye, try and set him off on the right foot. Ethan doesn’t move. I throw on my clothes from the night before, tie my shoes, splash some water on my face. “Ethan,” I say loudly, firmly. “I’m leaving. I have to go back to Seattle now.”

“What?” He says this whimsically, the words softly tumbling out of dry lips. We are not in the same world. It doesn’t matter. He’s not alert enough to thank me for coming, and I doubt he’d remember if he was. He never focused on the problems. He left that job for me.

“I’m leaving. Do you want to go get breakfast before I go?”

His only response is heavy breathing, the sound of my brother asleep, the sound of my brother in a place where no one can touch him. There is an uncomplicated peace to his slumber. Maybe this is the one place where it is simple to be Ethan. He is silent, and for one of the few moments in our shared existence, the capacity to hurt doesn’t exist within him. I place my palm against his cheek and inherit the warmth. He breathes, content.

Read more about Sam Shapiro here.

Read more about Daniel Lucas here.

“I place my palm against his cheek and inherit the warmth.” Beautiful ending.

“I have been trying to save my brother all afternoon.” Great line, fits perfectly.

Sounds like it was a tough childhood for both of you, and life still holds many challenges for Ethan, and you have that “big brother” obligation…

The ending is phenomenal. One of the many lines that struck me:

“I hid from their terror, from their violence. I still hide.”

I wish you both the best. Your essay is beautifully written.

Keep writing. Your ability to draw on real life experiences is something special.